- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

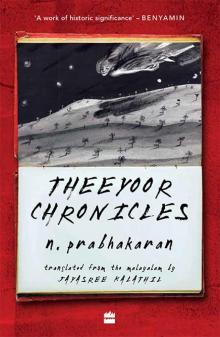

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 19

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 19

Murali had no close friends in Theeyoor, Chenkara or at college. The only person he could open up to was Sunil. Sunil was almost nine years older than Murali, but the age difference did not matter in their friendship. But Sunil was not always around. He changed jobs frequently, and went off to Delhi, Calcutta and Bangalore, working as a sales coordinator or a junior executive in a company or an accounts assistant, and came home only once every two or three months and only for a day or two. When he was home, he spent most of his time with Murali. He had no special feelings towards his adoptive parents, Wardha Gopalan and Draupathiyamma. There was a time when they had competed with each other to shower him with love, but now he was a guest in their home, albeit one with the freedom to do as he wished. His presence pleased them, but they did not make any demands on him or his time, or expect any special consideration from him.

Murali was doing his first-year pre-degree course and Sunil had recently completed his MSc when they met for the first time at the Theeyoor Public Library and Reading Room. Murali had come to take part in an essay writing contest conducted as part of the Onam celebration – the subject was ‘The changing times and young people’ – and Sunil was part of the organizing committee. Within a few days of being introduced to each other, they formed a deep connection. Sunil felt that he had found a friend with whom he could share his thoughts and ideas and even his private anxieties, that although much younger in age, Murali was the only person in Theeyoor who could understand him. And Murali felt that in Sunil he had found an older, wiser person he could trust, as well as a close friend with whom he could share his feelings. On countless evenings, they climbed Theevappara, and wandered across its expanse discussing politics, literature and topical issues. Together, they analysed the crushing loneliness, emptiness and disaffection that they felt – feelings they had assumed only they, individually, experienced.

Although outwardly energetic and friendly, Sunil too, like Murali, experienced a deep sense of alienation. He did not recover from it even after he was free to leave home and live independently, to decide the course of his life, in cities with totally different atmospheres from his village. There was something significant missing, he felt, something that crippled his soul. He had never forgotten who he was or where he came from before he was adopted by Wardha Gopalan and Draupathiyamma. The image of his birth mother, who had dragged him down paths of darkness, was still as clear in his heart as though carved in stone. Markets, riverbanks, foggy forest paths, mud and bamboo huts with grass-thatched roofs, women dancing in circles with their frizzy hair fluttering in the wind, lumbering men in dreamlike states, their bodies giving off the stench of tobacco, arrack and dust mixed with sweat … He remembered it all. He watched helplessly as the two human beings who lived with him in the house in Vayalumkara travelled steadily and inexorably into a world beyond that of love or hate. It was only when he was with his books, engaged in reading or writing, that he found some sense of satisfaction within the walls of that house shrouded in a curtain of silence. In the social life of Theeyoor, there were few spaces to feel at home. He had never had a great deal of interest in politics, and found the local political leaders – CTC, Thekkumbhagam Chathu, Bhaskaran Nair, the leader of the Muslim League Khadar Valavil, and the BJP front runner Dharman maash – to be a pack of jokers. He hated their public speeches, devoid of a single meaningful word, employing language only as a means to avoid engaging with real issues. The younger generation who sat in the reading room and pontificated about environment, politics, Adivasi issues and post-modernism were equally pointless, he found, their engagement with these issues superficial, removed, only an attempt to coat themselves with a patina of awareness or enlightenment. At the same time, Sunil found it difficult to settle into his own private sphere of thoughts, away from all that he considered dishonest, a sham. He involved himself with the activities of the reading room as a means to give his being something to do, to engage freely with the world, even though he had nothing of significance to contribute.

A long time ago, his childhood friend Venu had lent him books that he borrowed from the Kasturba Memorial Library in Chenkara. Those books had awakened in his mind the desire to render his soul in words, although he did not start writing until much later in life. He was twenty years old when his first poem was published in the weekend supplement of the newspaper Theeyoor Times run by Sreedharan maash. It was titled ‘Tree’:

My roots suck up the blood of the netherworld

Leaves cook it in the magical light

that seeps down from a broad, unknowable sky

I’m a rare tree, ignorant of how to flower or fruit

3.

Before becoming friends with Murali, the only person Sunil had any real conversation with was Sreedharan maash. Sreedharan maash had a negative streak in him, which annoyed Sunil. Despite his vast experience, wide-ranging knowledge and keen critical sense, Sreedharan maash nurtured deep within him a belief that progress was impossible. A sense of futility and the eagerness to cast everything as inconsequential – attitudes common among older journalists – were deep-seated in him. Sunil also found his approach to literature troubling. Sreedharan maash approached all issues logically and rationally, and although he ultimately reached an opinion that refused to acknowledge value in anything, he travelled to that conclusion in an orderly manner. But when it came to literature, he seemed to lose all sense of rationality and the ability for careful critical reflection.

For a man who had a considered opinion about everything, his estimation of literary works depended on the worth and value literary magazines and famous publishers gave them. He took the trouble to search for and read books on politics and economics, but when it came to literature he had none of this enthusiasm or drive. He tried to keep abreast of widely discussed foreign literary publications, but was clueless when it came to Malayalam literature after the 1960s, even as he worked to retain the façade that he was fully caught up with the latest developments and vogues in literary circles. That was the real reason why he published Sunil’s poem in his newspaper, even though he felt it to be nonsensical. On a later occasion, he told Sunil that, in publishing his poem, he had done him a favour. After that conversation, Sunil never again spoke to Sreedharan maash about literature.

Sunil’s poems, in the early days, were abstract representations of his experiences and ideas, unclear and inaccessible to the reader mainly because of a surplus of private metaphors. As he progressed in his reading and thinking, and as his efforts to find himself, to define himself, became sharper and more focused, he began to view with scorn the kind of writing that his own early efforts represented. He began to believe that, didactic and authoritarian or imaginative and rich in metaphors and similes, writing that came from outside concrete life experiences was faulty and irrelevant. His writing, he believed, should reflect real experiences of ordinary people – hunger, lust, the smell of sweat and excrement. Slowly, a deep-rooted belief formed in his mind, that a person’s identity, his sense of self, was something that could not be shared with the wider society unless it was through creative processes, and that any attempt to bring the structure and nature of one’s identity in line with accepted aesthetic parameters would be hypocrisy. In this vast and wondrous world, the details and essence of one person’s experience and emotion are different from the next one’s, and the only hope we have of shaping a life that is based on mutual understanding is to accept this diversity and difference along with the commonalities in our shared circumstances. Endeavours, conceptual or practical, to make all human beings accept the same values, principles and culture would only lead to the autocracy of those who want economic and political power. Literature that does not speak honestly from the inner life of the writer will, in the final analysis, turn out to be artificial, and the farther its language is from that of ordinary people’s communication, the more dishonest it will be.

As these ideas took firm root in his mind, Sunil abandoned poetry and turned to writing prose. He felt that

prose, by virtue of its form, was closer to the truth, and that poetry took communication away from the truth. But here, too, there were barriers he could not easily overcome. His style was spare, direct, without embellishments, and his readers felt that it was also devoid of imagination and creative flare. Editors, always on the lookout for attractive vocabulary, creative use of language and new narrative styles, did not like his stories and short essays. Some of it found the light of publication, but when most of what he sent out came back to him by return post, Sunil began to watch and evaluate himself more carefully. His vigilance made him withdraw even further, made him lonelier, and he came to the conclusion that he was unable to communicate effectively or form meaningful friendships, not only with the ordinary people around him but even with those who were immersed in the world of literary pursuits. His sense of self and alienation became denser, and still he wrote. His words, although simple and straightforward, had an aura of obfuscation, leaving his new writing as inaccessible as his old poems which were riddled with personal and private metaphors. Finally, he concluded that he was one of those people who simply could not cultivate broader human connections through writing, and that literature was, disappointingly, an area where people like him and their emotions always knocked on the gates but never gained entry.

All Sunil truly desired was the ability to engage with the ordinary and diverse concerns of the people around him in an unfettered and healthy manner. Why could he not find it through his writing? Why couldn’t he find some other way of fulfilling this desire? It is difficult to explain. (In fact, it is difficult to fully analyse and interpret anyone in this world, not just Sunil.) But we can try to further untangle the nature of the difficulties he was faced with.

Sunil had found succour and safety, at least in the beginning, in the unexpected change in his material circumstances. But a sense of disquiet, that in being transplanted thus from his previous life he was becoming someone else, began to take root. Draupathiyamma and Wardha Gopalan had ensured that he dressed well, that he had all he needed, unlike his classmates who came from Vayalumkara’s rural and poor circumstances. But Sunil was never at ease. In addition to the conclusions that he had come to after several hours of lonely contemplation, there was something else that constantly troubled him – his hair. Its unruly curliness that disdained the attempts of a comb reminded him – and everyone else, he believed – of who he was by birth. A Paniyan, an Adivasi from the forests. Occasionally, he entertained the idea of renouncing everything he had come by and returning to his community and people to try and build a life of his own, but he lacked the self-confidence to put this idea into action.

Sunil believed firmly that his neighbours in Vayalumkara were constantly recalling who he really was, and that they were scornful and sniggering on the inside. This belief was the main reason why he could not form any kind of relationship with any of them. In Theeyoor, unlike in Vayalumkara, he found an atmosphere that gave him a little bit more self-belief and inner peace, and he wanted to get involved in its social life and public services as much as possible. However, here too, things did not pan out as he had hoped. Almost everyone he came in close contact with had clear political ideologies but not the drive or inclination to engage with their politics other than as a spiritless everyday practicality. A handful of people, like Sickle Achuettan, inspired him with their clarity of thought and generosity of spirit, but the differences in their ages and ideology made it difficult for him to form any kind of lasting bond with them. And the rest dimmed his spirit with their mechanical existence, unchangeable mentality, and the impudence that burst forth every now and then. His personality did not possess the strength of conviction to stop thinking of these as insurmountable differences, and to productively contribute and collaborate with them in developing a healthier society together. Caught within this vicious circle, he found himself more and more alienated and with a rapidly depleting sense of self, which soon transformed into scorn and coldness of spirit. Combined with the fruitlessness of his efforts in the literary field, perhaps the area of engagement he had given the most attention, his failure to form meaningful modes of public and political participation made his mental and emotional life very dark indeed. Yet, Sunil did not wallow in self-deprecation and blame himself for his failure to find a niche in public life. Instead, he protected himself with an armour of high idealism, within which his isolation and alienation were sealed.

In school, Sunil was reluctant and anxious about interacting with girls, but this situation changed dramatically when he reached college. He began to form easy friendships with some of his classmates and with some older women, and went about nurturing these relationships until they showed signs of developing into something more than friendship. At that stage, he exhibited an almost uncontrollable haste to extricate himself and withdraw from them with no forewarning. This behaviour, over the years, had caused grave emotional pain to him and to many of those who had become close to him. Over time, Sunil came to recognize the ugliness and unethicality of his behaviour, and his solution was to withdraw from any opportunity of forming friendships with women, which in turn fostered a bitterness that fomented into a hatred for love, marriage and family life.

In effect, Sunil had become a closed-in human being in all senses, with a level of maturity and detachment that was unsuitable for his age. Only with Murali did he exhibit any of the fire and spirit of youth. But even with Murali, when the subject matter had anything to do with women, Sunil assumed an attitude of dry rationalism and dispassion.

So when Murali told him about Radhika, things came to a head. It was with extreme passion that Murali spoke about her, every atom of his heart throbbing with visions of romance and idealistic love that had all but become alien to young people. Suffused with the rare happiness overwhelming his spirit, his words fluttered like butterflies.

‘Love is all very well, as long as it remains just that,’ Sunil told his friend after listening to him patiently. ‘But our society deems love between two people successful only when it culminates in marriage. And once married, you and she will become just like any other married couple. You won’t be able to create a world of free and brave values that are not of this society and live happily ever after in it. Those pulp magazines like to debate endlessly: which is better, love marriage or arranged marriage? Guess what, it doesn’t matter! Both marriages are the same, and all couples end up in the same place – real life!’

Murali, who had not admitted even the thought of such mundane concerns into the courtyard of his new love, found Sunil’s words grating. How dare he say that his love was as ordinary or as pointless as other people’s? Murali had expected Sunil to be truly and deeply happy for him when he told him about his love. Instead, he had, through such comments, reduced him to the level of an ordinary person. His dismissal devastated him, and made him realize that he would have no one to support him when the most meaningful thing in his life was about to happen.

In the initial days of their love, Murali and Radhika had been careless, but as their relationship blossomed into something more serious and permanent, they became fully aware of its risks. They met secretly and with great care, the words and looks they exchanged became pregnant with meaning, and they became extremely cautious in their interactions with others.

The relationship changed Radhika, a naturally outgoing and fun-loving person, and made her withdraw into herself. Only her closest friends knew the reason for this change, and even they, who had never ventured into worlds outside of momentary attractions and cursory friendships with boys, were not able to understand it fully.

As soon as their final-year exams were over, Murali realized that he was done with education. When the results came, he had only managed a second class. With not many options before him, he decided to learn driving. The owner of the tailoring shop where his father worked, Kumaran Maestri, had a taxi car in Theeyoorangadi. A few days after Murali got his licence, its driver Sathyan went to Dubai, and just like that Murali became a ta

xi driver in Theeyoorangadi. During this time, he and Radhika rarely met in person, but they found ways to keep in touch and exchange news regularly.

But love does not remain hidden for long, and soon Radhika’s family came to know of their relationship, and as expected, they were completely against it. Radhika knew it was foolish to enrage them, so she convinced them that she and Murali were merely college mates, and whatever friendship they had had ended with their college days. Her family accepted her version of events, but they began to watch her every move.

Radhika had, by then, finished her pre-degree course and joined Payyannur College for a BA in English literature. One day, on her way to college, the bus she was travelling in broke down near Peerakkamthadam. Murali happened to come that way in his taxi, and he gave Radhika a lift to the college. The story that reached Rajeswaran and Rajeevan was that they had spent the day in a lodge room in Payyannur, and that Radhika had not arrived in college until evening.

An engineer from Aamachal by the name of Jayadevan was planning to visit Radhika’s family the next Sunday with a proposal for marriage. It was his brother, Sudevan, who was the instigator behind the story that reached Radhika’s brothers. When she got back home that evening, her brothers did not wait to ask her for her version of events, but set upon her, beat her, and locked her in a room for the next three days. On the fourth day, when they released her, people were gathering in a narrow lane leading from Theevappara to Chenkara. Someone had discovered Murali’s lifeless body in that lane.

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles