- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 20

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 20

There was no way Murali’s death could have been a suicide. There were marks of a struggle around his mouth, wounds on his lips and gums, and loose teeth in both his jaws. The police arrived, and after a post-mortem examination, the body was buried, but no arrests were made even after a week had passed. Rumours began to spread that the FIR and post-mortem reports had been tampered with, and that officials at high levels were trying to hush up the matter. An all-party meeting was organized in Theeyoorangadi demanding that Murali’s killers be brought to justice, and protest marches were held in Chenkara, Theeyoor and Vayalumkara. But nothing happened. One more week passed. Then Chindan went to the police station on his own and proclaimed that he was going to stage a sit-in and fast until death unless his son’s murderers were caught.

That night, Radhika went missing. All that was left in her bedroom was a note. It said: ‘I am leaving, but not to kill myself.’

THE FINAL CHAPTER

The Story So Far

I have, up until now, described what I have learned from my research in Theeyoor and from the information that has come to me by chance. I have taken the liberty to imagine certain events, but it is important to note that I am, first and foremost, a journalist, and that I have not knowingly ignored facts or let my imagination run wild in putting these ‘chronicles’ together.

No one who writes about Theeyoor can leave out the suicides that have taken place there. My own series, ‘A Village that Burns’ which was published in Janavartha, was no different. But I hope that Theeyoor Chronicles has told you more about life in Theeyoor than about death, and I take a level of comfort in that.

I have plenty more material about this ‘suicide village’ and the strange, interesting, as well as painful incidents that have happened there, and I could write a longer piece. But I don’t think including all of that would help you understand the people of Theeyoor and their lives any better or differently. Before I conclude, however, I want to record two more deaths, two strange suicides, in fact, that took place within days of each other in the three months before I came to Theeyoor. One of them was of Pichayya, the flower merchant turned moneylender of Theeyoor. The other was a man I have not introduced to you yet, a cockfighter by the name of Kachiprath Balan. Theeyoor Chronicles will not be complete without an account of their deaths.

A Floral Death

Pichayya, the man who came to Theeyoor as a flower trader, set up its first ‘blade’ company and became one of its most famous loan sharks, was extremely strict when it came to his own finances. He was a gracious host to people he thought he could benefit from, but he kept regular and exact records of all such expenditures, and made sure that what he invested came back to him twofold. Other than a moderate amount of drinking, he had no personal vices that required spending money. His henchmen were much too interested in drinking and feasting, and he tried to control their excesses by reminding them of childhoods spent in hunger and penury.

But there came a time when this man, who had lived his entire life carefully, began to show some changes in his behaviour. It was after Appanu Nambiar had passed away, and after Theeyoorians had begun to believe that Ramachandran had also died. Pichayya found himself, a man with no progeny or relatives, left with a large amount of money that was not rightfully his. The first change to manifest was in his drinking habits – he lost his control over it and began to indulge in earnest. Then came other indulgences of body and mind. For a while, during this period, he became a regular guest at Devayani’s house, but that ended when he had an altercation with a policeman who pummelled him and called him the most horrendous names. After that, he seemed to lose his mettle and began to seek solace in palm readers, astrologers and godmen. The amount of money he squandered, consulting everyone from mystics like Amu Jinn to sorcerers from the south who conducted rituals to appease the magical deity, Chathan, was extraordinary. His henchmen tried to counsel him but to no avail.

Ramachandran’s return to Theeyoor frightened Pichayya. He had not seen it personally, but the descriptions of his meditation with the methiyadi, the wooden sandals he had brought back from his travels, and the sword that he had found in the attic of his house were enough to send him into a paroxysm of terror. With Ramachandran’s death, Pichayya felt a brief sense of calm, but several other anxieties and worries had, by then, found a permanent place in his mind. And he found a substance, much more effective than alcohol, to help deal with it.

Nicknamed ‘schoolkutty’ – school student – this substance was codeine, and his supplier was a young man from Mangalapuram who worked in his flower shop. It was manufactured from opium and there were places in Mangalapuram where one could buy it in tablet form. Dissolved in a glass of tender coconut water or sugar water, a single tablet was enough to send one into a peaceful state of mind, where all the problems a person was faced with seemed mere inconveniences. Initially, Pichayya took codeine in small doses, but soon they increased in measure, and it was not long before the drug induced a constant state of drowsiness rather than energy in him.

Usually, Pichayya ventured out only in the company of his two henchmen, but one day, he made a trip to Mangalapuram on his own. He came back two days later, in the middle of the night and fully intoxicated. Holding aloft a bottle of Courrier brandy which he had brought back for the henchmen, he stepped into the front room. He ordered them to go to the flower shop and fetch a hundred yards of garland made from jasmine flowers. They did not ask him why he needed it. They had, by then, become accustomed to strange demands from him, such as getting workmen to make contraptions that caused harm and annoyance to people, or collecting the skulls of crows, owls, cows, donkeys and horses and doing weird things with them.

By the time the henchmen came back with the jasmine garland, Pichayya had bathed and taken a dose of codeine. He then lay down on the floor and asked them to cover him from top to toe, except his face, with the jasmine garland. They did as they were asked.

When they checked on him at around 2 p.m., Pichayya had covered his face with the leftover flowers. Having imbibed most of the brandy by then, the henchmen found their master’s action funny and left him to it. It was only the next morning that they realized he was dead. Quickly grabbing around 20,000 rupees that were in the house, they beat a speedy retreat and were never seen again.

Pichayya, covered head to foot in jasmine in his death, lay alone in the house. The strangely decorated corpse was discovered by a client, a merchant from Aamachal, who had come to repay a loan in the afternoon, and he alerted Theeyoorians.

Pichayya’s death did not cause much pain to anyone. In fact, those who had borrowed money from him let out sighs of relief. Others made up stories about how he was murdered by his own henchmen. Only a few felt a sense of unease, as though the floral death was a sign of some future calamity, and yet they said to each other: ‘Ah … what a charming way to go!’

Gamecock

Kachiprath Balan was not a real Theeyoorian. His father, Kachiprath Nanuvasan, was a kalari gurikkal, a teacher of martial arts, and they came to Theeyoor in 1940 when Balan was three years old. People said that, before he came to Theeyoor, Nanuvasan had murdered his wife. His wife was said to have had an affair with a man named Sankaran Embranthiri from Kuniyankunnu when Nanuvasan was on a three-month abstinence as required by his craft. When he found out, he is said to have kicked her to death. Whatever the truth, it seemed that Balan, as he grew older, also believed the story, and father and son did not have a good relationship. One day, when he was around eighteen years old, they had a great big row, which turned into a physical altercation. People said that Balan smacked the crown of his father’s head with a piece of wood. Nanuvasan died after lying unconscious for three days, and Balan became an orphan.

The rest of Balan’s eventful, chaotic life is as unbelievable as a fantastic story. He was implicated in four or five knife crimes, an attempted rape, and several big and small squabbles. Most of his connections were in Kasaragod, and his closest associate was a man named K

ittan from Kundamkuzhy. It is not clear whether Kittan was the instigator, but Balan began to get interested and involved in kozhikkettu – cockfighting. He began keeping gamecock – several breeds including Nattukozhi, Vorkkadi and Selan. He fed them paddy, pig fat and sesame oil, and entered them in cockfights in Kattukukke, Paikkam, Kumbala and Badirampallam. He won and lost in equal measure, and he continued to attend cockfights as though it were his profession. The people of Theeyoor had only heard of cockfighting. They paid no attention to his activities, and they had very little to do with him. Balan, with his long hair and knotted beard, his unwashed body dressed in soiled clothes, lived in a little shed-like house in a neglected, weed-grown compound in the shadow of Kilimala, with only his prized gamecock for company. The only people he was friendly with were a few cardsharps who lived in Theeyoor, and even their relationship did not extend beyond a few games of cards. By and large, Theeyoorians considered him a bad omen and left him to his devices, and Balan lived on amongst them like a malevolent spirit, attracting nothing but fear and scorn. It was only in death that he became a subject of interest. It was the most bizarre and horrifying death that I have ever come across.

No one who saw him lying dead under the mango tree in his yard would ever be able to get rid of that image from their recollection. His body was covered in slashes of kozhivaal – razor-sharp bits of metal tied as cockspur to the feet of gamecock – and there was a deep and narrow wound in the middle of his throat. His skin had been slathered with pig fat, and there was bloodstained paddy all over his chest and stomach, and signs of aggressive pecking. And on each side of his body lay two Uruvakkomban gamecocks, their beaks broken and innards wrenched out. The cockspurs tied to their feet were still intact.

Later, one of the people who had seen the corpse told me that Balan’s body had lost its human shape in death, and that he had looked like a human-sized gamecock. ‘He was a cock anyway,’ he said. ‘A cock straight from hell!’

The Last Record

We have come to the end of Theeyoor Chronicles. When I look back, I have no convincing answer to the question why I wrote this. In many of the old stone inscriptions, there would be a line at the end describing the writer, recording who the historian was, and these were usually ordinary people who, although skilled in the art of inscription, did not possess the talent or birthright that would entitle them to a mention in the history that is inscribed. But for the generations that came later, they are very much part of the history. Like those long-ago ‘inscription workers’ who became part of a history that they did not create, I too am only a scribe as far as Theeyoor Chronicles is concerned. Still, coming to the end of this work, I find myself tired, sad and overcome by a vague sense of insignificance. It is not my intention to delve in detail into these feelings. In fact, although these records will invariably contain traces of my thoughts and emotions, self-representation was not my intention right from the start. And I don’t intend to change my mind now.

After writing the first few chapters of Theeyoor Chronicles, I took a week’s leave of absence and went on a short trip. The trip had no specific objective, but somewhere along the way, a Malayali friend who currently lives outside Kerala took me to a magician’s house. A disciple of the old magician was presenting one of the oldest and most famous magic tricks – the Great Indian Rope Trick – in front of a specially invited audience of about fifty people.

An attractive young man, dressed in black, followed the magician into the yard where the guests had assembled. He had a basket and a magudi – a musical instrument used by snake charmers – in his hand. He passed the magudi to the magician, bowed and touched his feet, and then went around showing the basket to the audience so that they could see what was inside – a fairly thick rope rolled into a spiral.

The old magician began blowing the magudi. At its first note, the end of the coiled rope in the basket sat up straight, and as the music continued, the rope climbed higher and higher. Finally, when the rope was around twelve feet high, the magudi stopped. The young man began climbing up the stiff, straight piece of rope as though it were a tree trunk. As he came to the end of the rope, the magician blew the magudi again, and by the time we looked back from him to the young man, he had disappeared! And when he reappeared, four or five minutes later, on the sit-out of the house, it was with a deafening applause that we welcomed him back.

After the event, when the audience dispersed after repeated exclamations over the performance and its magic, I went up to the young man and introduced myself as a journalist. As we shook hands, he told me that his name was Sunil, and that he was working, for the time being, as an area manager for a courier company.

‘Are you considering magic as a career?’ I asked him.

‘Oh no, not really,’ Sunil responded.

‘I’ve heard that the rope trick is an especially difficult trick to master. Did you learn it just for the thrill?’

‘No. I wanted to go back home and perform it there.’

‘Any particular reason for it…?’

‘Not really. Just that there is a special feeling when you share something magical with your own people. I want to experience that.’

‘And where is home?’

‘I’m not from here,’ Sunil said. ‘I am from a place called Theeyoor.’

There was a secretive smile on his lips as he said the word ‘Theeyoor’. I was confused and tried hard to figure out why I could not recognize him even though he looked exactly as he was described in all the information I had gathered about him.

Two days after I was back in the office, Shyamala, the editor of our newspaper’s weekend supplement, came up to me.

‘I met a woman on the train today,’ she said. ‘An attractive young woman named Radhika. She had a baby in her arms, and she was travelling alone. I don’t know, I felt there was something odd about her, and I tried to befriend her. She was quite reticent but I got her talking and we chatted for a bit. I asked her where the father of the child was. Do you know what she said to me? She said, “A child does not come about only because of a father. I am her mother. That’s all you need to know.”’

‘Must be a hardcore feminist,’ our cartoonist James said, laughing as though he had cracked a great joke.

‘I have no idea…’ Shyamala sighed.

‘Do you know where she was from?’ I asked her.

‘Ah yes, that’s what was interesting about this,’ Shyamala said. ‘She was from Theeyoor – your suicide village.’

P.S.

Insights, Interviews & More …

Translator’s Note

Jayasree Kalathil

Political Background

N. Prabhakaran and Jayasree Kalathil

N. Prabhakaran in Conversation with

Jayasree Kalathil

Translator’s Note

JAYASREE KALATHIL

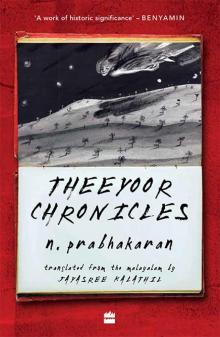

‘History is myth, a reconstruction of the past to suit the needs of the present. Its discourse is subject to the same narrative rules of inclusion and exclusion as is the discourse of myth,’ wrote P.P. Ravindran in a 2003 study of the contemporary Malayalam novel. This is a timely reminder as N. Prabhakaran’s Theeyoor Rekhakal is translated into English – twenty-two years after its publication in the original Malayalam in 1999 – in a world where grand narratives of ‘nation’, ‘nationality’ and ‘national history’ are reappearing, sometimes under violent conditions, to the detriment of regional and local lived realities, and the destruction of diversity and difference.

Theeyoor Chronicles is presented as the history of a land, Theeyoor, roughly spanning eight or nine decades, beginning with the first decade of the twentieth century. In this land, comprising the villages of Theeyoor and Chenkara, in a short span of time, an alarming number of people have died by suicide or disappeared. The story of this land and its people unfolds through a journalist’s quest to explore this phenomenon.

Theeyoor is an imaginary place. One can read it as symbolic of the many ‘suicide villages’ that exist in

Kerala, perhaps also outside Kerala. At the same time, it is also specific in the sense that people familiar with northern Kerala will recognize it, from the geographical descriptions in the novel, as Eripuram, the native village of N. Prabhakaran. The Portuguese called it ‘the city of burning fires’ (‘Theeyoor’ also means the land of fire). The adjacent Madayipara, a rocky expanse of significant natural diversity and beauty, appears in the novel as Theevappara. This ‘historic’ landscape provides the background to the ‘fictional’ history of its people.

Several events of the first eight or nine decades of the twentieth century that remain significant in the social memory of northern Kerala play important roles in the plot, including the freedom movement, the formation of a local cell of the Communist Party, peasant struggles, the large-scale conversion of Harijans to Christianity, the cholera epidemic in the 1940s, the political fallout of the declaration of Emergency by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the demolition of the Babri Masjid in the 1990s, and so on. Political and cultural figures such as A.K. Gopalan, E.M.S. Namboodiripad, Sree Narayana Guru, Keraleeyan, Mahatma Gandhi and many others are referenced in the novel. However, unlike in formal histories, these events are not presented as grand narratives or the people as heroes of national history. Instead, they form the backdrop to the telling of a local history which focuses on ordinary folk’s experiences of historical events and people. The history of the place is the history of its people and their relationships, their children’s lives, their loves and losses, their sense of belonging and alienation, their political, cultural, religious and spiritual life, their education, trade, art, pastime, folklore, and so on.

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles