- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

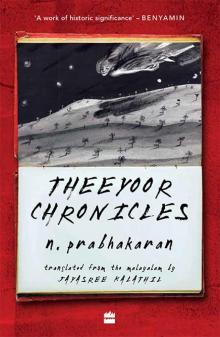

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Contents

Preface

Prologue

TRUTHS LED ADRIFT

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

INCOMPLETE

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

CLEOPATRA AND SOME OTHERS

1.

2.

SNAKES AND LADDERS

1.

2.

3.

4.

Alternative Narrative

HE WHO LIVED BY THE SWORD

1.

2.

3.

THE LIFEBLOOD OF LOVE

1.

2.

3.

THE FINAL CHAPTER

The Story So Far

A Floral Death

Gamecock

The Last Record

P.S. Section

About the Book

About the Authors

Copyright

Preface

It was on 3 October 1997 that I visited Theeyoor for the very first time. I wanted to write a series of articles about this place which had become famous as the home of those who disappeared and those who died by suicide. I was there for five days, from the third to the seventh, living in a rented room near Theeyoor Government High School, and travelling across the village, speaking to people and collecting information.

Theeyoor panchayat, which includes the villages of Theeyoor and Chenkara, covers an area of 40.14 square kilometres, and has a population of 29,901, more than half of which lives in Theeyoor. In the period between January and September 1997, fourteen people had killed themselves and four people had disappeared in Theeyoor alone.

Nine of the fourteen suicides were by hanging, three had consumed poison, and one had jumped into the river. The remaining death was quite bizarre. He was a cockfight enthusiast and had somehow managed to get himself pecked to death by two of his gamecocks. Theeyoorians could not comprehend why so many people had taken their own lives in such a short period of time, nor could they understand how four people who lived amongst them could simply disappear. All they had to fall back on was rumour and speculation.

In the five days that I was there, I made careful notes of everything I heard, everything I was told. By the afternoon of 8 October, I was back in my office, and on the eleventh, I submitted my article, ‘A Village that Burns’ – Theeyoor literally means ‘the land of fire’ – to my editor. Janavartha published it as a series over the next four days, but I had written it in one sitting, in one night. The series did not get much of a response in Theeyoor, but letters poured in from other villages and cities, and even from abroad.

The successes of a journalist are short-lived, and so it was with the fame ‘A Village that Burns’ brought me. Still, Theeyoor and its people, and those in whose pursuit I had gone there – the dead and the disappeared – would not leave my mind. They lingered on, made themselves a lively part of my day-to-day musings. Gradually, the need to write something more about the village became an almost constant ache, and when I could not ignore it any more, I began writing this book. The content of this book is based on a variety of sources: my own research while I was in Theeyoor; material from the book The History of Theeyoor written by a Theeyoorian, Wardha Gopalan; and the information Sadanandan maash, a retired schoolteacher and a local agent of our newspaper, shared with me in person and in the letters he wrote me.

I did not choose the title of this book as a conscious attempt to mislead students of history or anyone else into believing that this is a historiographic document. I had put my notes on Theeyoor in an envelope, and after I finished my article, I had casually dropped it among the other stuff in my study. When I began to consider in earnest the possibility of writing a book, I looked for it, and after much searching, found it amidst the clutter that had gathered on the floor. Perhaps because of its long, neglected residence in the slight dampness on the floor, smoke-coloured mould had spread over the envelope and the papers inside had yellowed. They looked like old, historic records, I thought to myself in jest, and suddenly the name of the book came to me:

Theeyoor Chronicles!

Prologue

Words, too, are like human beings. Behind every word, there are thousands of dead words which are faded markers of former human existence.

When I began writing the story of Koneri Vellen, my plan was to use the language and idioms used locally at the time. However, I soon realized that there was something strained and not quite pleasant about that style, and so I abandoned the idea. No matter how much I tried, I would not be able to enter Vellen’s mindset fully from today’s perspective. It would be impossible to recreate the warmth, the whiff, the texture of light and shadow of his time; its nature and environment were beyond my descriptive powers, the essential authenticity of its forests, rivers, hills and lanes lay beyond my grasp. A handful of people who knew Vellen are still alive in Theeyoor. Some of them are lost in the quagmires of old age, and the others don’t know much about him and only have some anecdotes to share. Wardha Gopalan’s The History of Theeyoor also has only a few minor mentions.

Vellen was a wanted man with a price on his head. In 1925, a policeman by the name of Chandu shot him dead. He was fifty-four or fifty-five years old at the time. His oldest daughter, Manikyam, was twenty-nine, and her mother, Muthamma, was forty-seven. Muthamma was not Vellen’s wife but a woman he had kidnapped, and she was the reason he had come to Theeyoor. He had seen her for the first time in Aamachal, on his way back from breaking into the house of a man named Ambunair in Kuniyankunnu. In those days, in the month of Meenam, a party of Kodagu traders would come to Aamachal with rice, chillies and various forest produce, and camp at the inn belonging to the Valyejamanan – the feudal landlord – of Aamachal. Vellen had seen a light in the lean-to behind the inn and had gone to investigate, even though he knew that such curiosity, especially after committing a big burglary, was not advisable. But he had not been able to resist the urge. Something or someone had pulled him towards the light. As he squatted behind some bushes, he had seen a young woman dressed in a red woollen blouse in the lean-to, sweeping up the ashes of the cooking fire. She raised her face, and Vellen’s eyes had throbbed as though witnessing something magical. He had never seen such a lovely face, not even in his fantasies.

Burglary was Vellen’s lifeblood. He knew no other way than to just take what he wanted from life. Before he realized it, he was inside the lean-to, and covering the young woman’s mouth with his hand, he had scooped her up and run out into the darkness.

He remained in hiding with her until the following night. At midnight, he brought her to Chemmaran’s hovel at the bottom of Kilimala, around twenty kilometres west of Aamachal, in Theeyoor. By then, scared and wretchedly sad, and having walked a very long way, the young woman had wilted like the tender stem of a taro leaf.

Chemmaran lived with his wife Cheeyeyi and their two children in a lonesome hovel he had built after falling out with all his relatives. He was taken aback by the unexpected arrival of his friend. They had met around two years ago at the festival in Malliyott, when a fight had broken out outside the temple and Vellen had come to Chemmaran’s rescue. Although he looked like a young boy, he had grabbed hold of Chemmaran’s hand and jumped into the field below, dodging the swinging fists of four or five hooligans. Later, as they made their acquaintance over a pot of toddy, Vellen had disclosed that he was a thief.

Here he was now, in the company of a blouse-wearing, fair-skinned woman! He looked all grown up, with a bushier moustache, broader chest and thicker forearms. As soon as he saw

them, Chemmaran realized that Vellen had stolen the woman from somewhere.

Vellen left Muthamma in Chemmaran’s care, with strict instructions not to let her out or to let anyone see her. He promised to be back in about a week’s time, and as promised, he returned before daybreak on the seventh day. He was a new man, dressed in a mundu that covered his knees and a white upper garment, and he had a large amount of money in his possession. The very next day, he went to visit Rairunambiar, the overseer of Theeyoor Valyejamanan’s affairs, with a gift of a bottle of rum.

In those days, rum was a commodity known only to the white sahebs, the high-ranking officials who worked under them, the rich who lived in big towns, and other such fashionable people. Vellen introduced himself as Narayanan Nair from Thalassery who worked with the white sahebs. He asked Rairunambiar to appeal to the Valyejamanan on his behalf to allow him to buy the four-acre coconut grove named Koneripparambu, adjacent to Chemmaran’s hovel. Rairunambiar was already enthralled by the sight of the bottle of rum, and the addition of a five-rupee note to the gift sealed his friendship with ‘Narayanan Nair’. Within four days, the deed for Koneripparambu changed hands.

There, in a newly constructed two-storey house, Vellen began his life with Muthamma. It would be another five years before his secrets would be revealed to some of the local people – secrets that Chemmaran, true to his word, had kept even from Cheeyeyi. But by then, all of them were indebted to Vellen in one way or another.

Vellen was home in Theeyoor only for a couple of days in a month. When he was away, he left Muthamma in the company of Cheeyeyi and a sixty-year-old woman named Njavinichi he had brought over from faraway Chengalayi. By the time they moved into their new house, Muthamma was already pregnant. Vellen named his firstborn, a girl, Manikyam. More children followed – Madhu, Kannan, Kammaran and Kunjutti – leaving Muthamma in a continuous state of pregnancy and childbirth. Irritated by her children and listening to Cheeyeyi’s chatter and Njavinichi’s stories of ghouls and spirits, she lived within the walls of that house, barely seeing the outside world. Memories of her home in Ponnambetta and her loved ones remained in her heart, and endured and thrived as time went by. She was never able to find a place in her affections for Vellen, who came and went as he pleased, but she hid her anger and hatred from him and from the people of Theeyoor.

With a quiet determination, she spent all the money Vellen gave her on each of his visits. She did not deny anyone who asked for her aid, never once holding back when someone needed a helping hand. She cooked elaborate meals for Cheeyeyi and her children, the workers in the coconut grove and the cowherds; sent offerings of oil, money and chicken to the temples in Chenkara, Theeyoor and Aamachal. As time went by, the house name ‘Koneri’ came to be used only in reference to Vellen, while his household came to be known among Theeyoorians as ‘Kodagatheentada’ – the home of the lady from Kodagu.

Vellen, too, had yielding hands. As though to make up for his sins, he donated half of what he made from each of his burglaries to those who were in need – the poor, the destitute and the ones mired in debt. These people found that what they needed – a bundle of money, a sack of rice, a couple of mundus – would appear on their doorsteps without their having to ask, and they knew who had brought them these gifts.

When he set out on his burglaries, Vellen would become another person, with a heart as tough as a block of granite and muscles as strong as those of a wild buffalo. Once he picked the time and place of his next break-in, his eyes and ears would become as sharp as firethorn, and his mind would focus only on his mission. The rich in the towns and villages nearby feared his name, while the poor of Theeyoor worshipped it. Few had actually seen Vellen in broad daylight, and yet they felt they knew him well, that he was one of their own. When finally, on a new-moon night, on the northern slope of Kilimala, Policeman Chandu shot him dead, they were all as shocked and grief-stricken as though they had lost their own sibling.

Vellen did not leave Theeyoorians even after his death. He received a place in the collective memory of Theeyoor with its venerable elders, right beside fearless fighters, powerful wizards, famed healers and seers. Stories grew around his name, and in time, these stories became legends.

In these stories, he shape-shifted into a bull or a cat in a split second, charmed people out of their senses, put them to sleep with a single glance. Once, at Kalikkadavu … Remember, in Pookkothunada near Thaliparamba … At a Hajiyaar’s house in Valapattanam … New lands and faraway towns entered his legends. He anointed his body with peacock oil, they said, ate the meat of a pangolin, drank the fat off a python, hid in an abandoned well, swam across a swollen river, broke free from iron shackles…

As time went by, the stories faded and lost their lustre, and there were fewer and fewer people to tell them or listen to them. Still, every once in a while, Vellen appeared on their tongues. ‘Who does he think he is? Vellen?’ one might hear in a chai shop in Theeyoorangadi, the old market area. Or as the last word in an argument on Theeyoor beach: ‘Even Vellen couldn’t do this.’ Or an old-timer with dimmed eyes and tired ears would start, confident that someone was listening to his reverie, ‘When I was a child … That is to say, when Koneri Vellen was alive…’

TRUTHS LED ADRIFT

1.

Gopalan ran away from home the day after Koneri Vellen was shot dead. He was nineteen years old.

‘My first stop was Mangalapuram, where I worked in a hotel for almost two years. From there, I went to Karwar, Belgaum, Ichalkaranji, Kolhapur, Bombay … Drifted aimlessly for the next eight or nine years, did all sorts of jobs, put up with all sorts. Finally, I ended up in Wardha, with Mahatma Gandhi.’

In 1952, at the age of forty-six, when Gopalan returned to Theeyoor wearing a Gandhi cap and khaddar clothes, he had the maturity of someone who had experienced life. He had also acquired the habit of starting all his sentences with ‘When I was in Wardha…’ or ‘Bapuji and I…’ until people began to refer to him as Wardha Gopalan. He found a considerable amount of joy and pride in the nickname.

By the time Gopalan came back, his family, which had been fairly well-to-do, had become impoverished and now subsisted hand to mouth. An unmarried uncle who had taken care of the day-to-day affairs of the family had been bitten by a viper and died. Gopalan’s father had started a new relationship at the ripe age of fifty-two, and had moved away to Mathamangalam. His mother, who suffered from asthma and other respiratory illnesses, had become mostly bedridden. An older, disabled aunt did all the work in and around the house, her frail, skeletal, seventy-year-old body rattling about the compound. Gopalan’s older sister had married and moved to her husband’s house in Chenkara even before he had left. His older brother who lived with his wife in Pattuvam had his hands full managing a small holding and some cattle, and rarely came to visit. His youngest sister was childless and lived at home, having been abandoned, for all practical purposes, by her husband. So did his younger brother, his wife and their two children. The brother had no permanent job, and spent his time as an amateur actor and musician. His wife was a midwife at Theeyoor Primary Health Centre, and the entire household subsisted on her salary and the meagre earnings from selling the produce on their land.

The local political scene was also different from what Gopalan had anticipated. Most of the farmers, ploughmen, and others who worked the land had become communists. Reading rooms and chai shops had become hubs of political discussions. There were only a few left who supported the Congress Party – a few upper-caste Nairs and Nambisans, and a handful of Harijans in Theeyoor Thekkumbhagam, the southern part of Theeyoor.

Gopalan got in touch with some of the more prominent members of the Congress Party. They were keen to put a stop to the exponential growth in popularity of the communists, but none of them were willing to step up and do something about it. In the elections of January 1952, the communist leader A.K. Gopalan had taken the Kannur parliamentary seat with more than double the votes won by the Congress Party candidate C.K. Govin

dan Nair. They were still reeling from the shock. Then there was the incident with Swami Anandatheerthan, a disciple of the social reformer Sree Narayana Guru. He had sent a report to the government complaining that the Thaavam Devivilasam Elementary School was refusing to enrol Harijan students, and demanding that the school’s permit be revoked. The incident had left these prominent personages irately muttering about the ‘Harijan love’ within the Party. The times were changing. They felt everything was working against them, and they seethed inwardly with rage and resentment. So, when Gopalan approached them, they did not hide their displeasure with the vagabond – that too, someone from the lowly Thiyyan caste! – who had the audacity to think that he could teach them about politics.

So Gopalan went to the Harijans in Theeyoor Thekkumbhagam. They had their own leader, a clever man by the name of Chathu. Realizing that Gopalan’s entry into local politics would be detrimental to his own interests, Chathu began spreading rumours about him. ‘Did you know, the day after Gopalan left home, his neighbour Karuthambu’s daughter Parootti killed herself by hanging? She was three months pregnant!’ And as though he had first-hand knowledge: ‘All this “Wardha”, “Bapuji” and all – all nonsense! You know Mammuappla from Theeyoorangadi? Actually, Gopalan was working in his chai shop in Bombay.’

At first, Gopalan was not aware of these stories spreading across Thekkumbhagam. But soon he began to notice a general lack of respect and some pointed remarks from the younger people. Eventually, realizing that he was not being included in any important discussions, and that people were being civil only to his face, he withdrew. For the next couple of months, he remained at home doing nothing. Then he bought a single-room shop in Theeyoorangadi, and started a khaddar textile shop. He hung on to the shop for nearly two years, but with not much sales or profit, he finally gave up.

As soon as he had come back, his mother had started pushing him to get married. His older sister Devu too had nothing else to say to him whenever he visited her in Chenkara. When she saw that her relentless nagging was not having the expected effect on Gopalan, Devu edathi told him, ‘If you’re still thinking of that Kunjimani, you needn’t bother. They all left Theeyoor a long time ago.’

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles