- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 18

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 18

On the afternoon of 6 December, at around 2 p.m., when the first dome of the Babri Masjid was brought down, Ramachandran was among the twenty-five-odd demolishers who got caught under it as it fell to the ground. They were all pulled out and rushed to the hospital. Ramachandran had sustained severe injuries to the back of his head and shoulders, and seemed unconscious as he was carted away.

The sighting of Ramachandran in Ayodhya and his part in the demolition of the Babri Masjid was something the RSS in Chenkara and Theeyoor wanted to keep to themselves. But the news got out, and it finally reached Appanu Nambiar when, one day, he overheard a young man, a stranger, describe the events to another man. The shock was so deep that he fell over in a faint. By the time people gathered and took him to Dr Ramanathan at the primary health centre, he was already dead.

It was another four years after Appanu Nambiar’s death that Ramachandran returned to Theeyoor. The year was 1997. Nambiar’s death had transformed his wife, Sulochana. She had finally found peace, and lived out a quiet, almost lifeless, existence immersed in prayers. One day, as she lit the evening lamp in front of the house, she was shocked to see her long-estranged son standing there in the yard with his palms folded. He was dressed in a pleated saffron mundu and his upper body was covered with a shawl printed with the phrase ‘Jai Shri Ram’. His hair was long and he had a thick beard, and he held a small bundle in his hand.

He bent down and touched his mother’s feet. ‘Amme, Mahamaaye, my Mother Goddess,’ he said, and went inside the house.

Ramachandran did not leave the house for the next two months. In the bundle he had with him, there was a pair of methiyadi – old-fashioned wooden sandals. He placed them on a low stool in the attic room, and positioned the old sword straight above them. He sat in the lotus position in front of this arrangement, palms folded, chanting something voicelessly. Sulochana watched her son and his strange behaviour, and shed tears of confusion. Her questions about the sandals and the sword, and about where he had been all this time, went unanswered. Pichayya, Dileepan maash and old man Pulluvan Raman, whom Ramachandran thought he had killed, came to see him, but he refused to meet them. He spent his days and nights in prayer as though he had forgotten all about who he was earlier.

Then one night, the prayers ended. Ramachandran left home without alerting his mother. Two days later, his dead body was found hanging in a shed in a small yard with a low stone wall on the southern side of Theevappara. Below the body was an old, rusted sword with a bit of blood crusted on its blade. Ramachandran had cut the veins on his left wrist with it. The only thing that puzzled those who came to look at the dead body was how he had managed to hang himself after having cut his own wrist.

THE LIFEBLOOD OF LOVE

1.

Theeyoor Chronicles started with the story of Koneri Vellen. In this chapter, we will meet a descendant of his, the beautiful Radhika, her lover Murali, and Sunil, the adopted son of Wardha Gopalan whom you have already met briefly.

First, a brief history of Radhika’s family. The oldest child of Koneri Vellen and Muthamma was a daughter named Manikyam. Manikyam had a daughter, Kausu, and Kausu had a daughter, Shantha. Radhika was the youngest of Shantha’s three children. Muthamma died in 1948, the year Kausu gave birth to Shantha. By then, Vellen’s children and children’s children had squandered the wealth he had amassed over the years.

Manikyam married Uruvadan, the son of Chemmaran who had given asylum to Vellen and Muthamma when they first came to Theeyoor. Their marriage took place fourteen years before Vellen’s death. Kausu was their second daughter, and she married a man named Kannan from Aamachal. Kannan was one of the first people to spread the political ideology of the Congress in Theeyoor, but when the Communist Party was established, he promptly joined it, and worked tirelessly and without fear for personal safety for it, thereby becoming the arch-enemy of his erstwhile colleagues in the Congress Party. In 1948, when he was in hiding, living secretly in Kilimala in a house belonging to a man named Pokkan, they set a trap and caught him, and beat him to within an inch of his life as though he were a poisonous snake. Assuming that the unconscious Kannan was dead, they left him in a shallow grave covered with dry leaves. Several hours later, a woman named Kallu who had come to collect dry leaves to be used as fuel heard his faint grunts. Hollering loudly, she alerted people, and as they were in the process of saving his life, his wife Kausu was giving birth to their seventh child.

Shantha, their daughter, grew up in grave poverty. Although he did not die from the attack, Kannan was never the same physically and was barely able to wield a hoe, and within two years his miserable life came to an end. He had not provided for his children and wife, spending whatever he had earned during his lifetime for the betterment of the Party. With her six siblings, Shantha grew up without a full meal on most days or proper clothes to wear, dependent as the entire family was on the money their mother and oldest brother made from working as coolies. Still, she paid attention at school, did well in her classes, passed her secondary school and pre-degree exams, and went to college for a BSc degree. Just before her final-year exams, she got a job as a clerk in the Department of Health. Her first posting was at the primary health centre in Kuniyankunnu. While working there, she fell in love with the health inspector, a man named Srinivasan from Nileswaram, and despite severe objections from his family, they got married. They had three children, the youngest was Radhika, and the older two were twins named Rajeswaran and Rajeevan. They were identical in everything, from looks to behaviour and mannerisms, with a good physique, a keen interest in good food and good clothes, and a sense of independence and self-reliance. They were equally uninterested in schoolwork, and despite Srinivasan’s and Shantha’s constant vigil, they failed secondary school.

But in spite of their horrendous track record in academics, Rajeswaran and Rajeevan were not total failures. Books and reading put them to sleep, but they had a keen sense for business. Recognizing this aptitude, Srinivasan helped them set up a shop selling cement and building materials in Theeyoorangadi. The year was 1991, and the whole state seemed to be in the grip of a building craze, and within two years the modest shop became one of the largest trading establishments in the market.

Srinivasan and Shantha had always lived comfortably on their salaries. Srinivasan forsook all unnecessary expenditure and Shantha, who spent every paisa only after considering and reconsidering the expense, was a perfect companion in his pursuit of a simple life. But their children were different right from the start, and as soon as they began dabbling in large sums of money, they brought their parents in line with their way of life.

A year after their marriage, Srinivasan had built a small brick house and moved there with his wife. As their children grew up, they had often thought about rebuilding the house, but the exorbitant expense of it had stopped them from embarking on it. When Rajeswaran and Rajeevan made the arrangements, they finally agreed. The house was refurbished with three additional rooms, a new front and façade, and fitted with a brand-new telephone, a car and other household conveniences. The atmosphere of their family home changed dramatically, and Srinivasan and Shantha decided, finally, to relax their careful, paisa-pinching ways. The person who was most pleased with these changes was Radhika, their youngest. She was a happy child, with a ready laugh and an attitude that looked for the fun things in life. The lavish love that her parents and brothers covered her with had made her a self-confident person, and she was like a beautiful being sent to this earth only to laugh and play and be happy.

At the time the house was refurbished and their family moved into a more obviously extravagant lifestyle, Radhika was studying for her first-year pre-degree course. A naturally charming young woman, Radhika became more attractive day by day as the signs of prosperity became more and more obvious in the clothes she wore and in her general demeanour. There was not a single man around who did not gaze at her with a new joy gently lighting his heart as she stood at the Theeyoor Meleyangadi bus stop waiting for

the bus to Payyannur College where she studied. Radhika seemed oblivious to their adoring glances as she chatted and laughed with her girlfriends. Her body was physically more mature than her age warranted, but she was not the type to slink back embarrassed and afraid. She burst with the energy of adolescence and the eagerness of youth, and her innate need to occupy her being without hiding it away was strong and irresistible.

But all this changed, and the incident that caused the change was somewhat funny. That year, Payyannur College played host to the cultural festival of the colleges in Kannur affiliated to Calicut University. On the third day of the festival, as Radhika and her friends were walking behind the stage where the Hindi drama competition was taking place, they heard someone call, ‘Hello, please … Hello, could you come here for a minute…?’

It was the man who had played the part of a ghoul in one of the previous plays. This ghoul was painted black from head to toe in a paste of oil and ash, with white lines of rice flour paste drawn across. The other players and the troupe had left soon after the play, upset as they were that one of the actors had muddled up his dialogue. In their anxiety and hurry, they had forgotten about helping the ghoul take off his make-up. And the ghoul was stranded, trying to figure out how to get hold of a bucket of water – he had a piece of soap in his hand – and with his eyes watering from a bit of ash that had gotten in them. He was at his wits’ end, which was why he called out to the girls as they passed, even though he was dressed pitifully only in a blackened pair of underpants. He beckoned to them with his hand: ‘Come here, come…’ Radhika’s girlfriends laughed loudly at the pathetic figure and walked away, but she stood where she was for a minute, and then walked up to the ghoul.

‘Do you think you could get me a bucket of water?’ he asked her.

Radhika managed to find a bucket of water for him. Then she joined her friends and they laughed about the incident.

Rajeswaran had promised to pick up Radhika and two of her local friends by half past eight. As they stood by the roadside waiting for his car, a young man, dressed in a grey shirt and a dirty mundu came up to them.

‘Do you remember me?’ he asked.

Radhika thought she recognized the voice, but not the man. ‘No,’ she replied.

‘What, forgot so soon? You helped me just now and brought me a bucket of water,’ the young man said. He continued after a short pause, ‘My name is Murali.’

Usually, such an incident would have made Radhika laugh out loud, but the unusual self-assurance in the man’s voice, the slight smile at the corner of his lips, and the simple sparkle in his eyes filled Radhika with a strange feeling, something she had never felt before and could not recognize.

Two days later, as Radhika stood alone at the college canteen, there he was, as though appearing from nowhere, in front of her.

‘Haven’t forgotten, have you?’

Radhika lowered her head at his question.

‘Do you have a piece of paper?’ he asked.

Without asking him what it was for, Radhika offered him one of her notebooks. ‘Here, you can write in this,’ she told him.

Murali did not tear off a page from the notebook. Instead, he wrote in it. This is what he wrote:

For Radhika,

Love never becomes antiquated.

Yours,

Murali (the Ghoul)

2.

Murali had acted like a self-assured lover in front of Radhika, but in reality he was a loner, prone to melancholy and plagued with self-doubt. The only reason he had agreed to be part of the drama competition was that the others had promised him he would not have to speak and would be onstage just for two minutes. The play, titled Bhoolne ke Viruddh Ek Dastavez, was directed by Padmanabhan, a classmate of his in the third-year chemistry degree course. Even as he stood in the semi-darkness onstage and raised his hand in the air as he had rehearsed, he regretted having agreed to it. But as it turned out, the ghoul in the play had changed his drab, uneventful life like magic, and whenever he thought about it, he was overcome with a special fondness for Padmanabhan, the play and even the Hindi language.

Murali’s love germinated in the clear and straightforward look that Radhika had given him when she brought him the bucket of water. Radhika had not meant anything by that look. She was, by nature, curious and unafraid, and the guileless look was genuinely part of her being. But Murali took it to be an invitation, pregnant with emotion, to a deep and fulfilling relationship. The reason he found the courage to approach a young woman like Radhika was the sense of liberation that only love can generate in a person. Love evens out the order of things, makes the positions, privileges and differentiations in life immaterial. Its world is as wide as that of the bird in the sky, its energy that of the wind and the wave, its existence as pure and naked as freshly tilled earth.

However, there were moments when he stepped out of the magical embrace of love, when the rough palm of reality touched his heart, and in those moments, the son of Chindan, a tailor from Chenkara, and the nephew of Ambuperuvannan squirmed in discomfort. There was nothing in the circumstances of his life that was venerable, that could be celebrated. His father the tailor did not own his shop but worked in someone else’s. His mother was frail and constantly ill with a stomach pain and other complaints. And his two sisters and their children were also at home most of the time because their husbands made barely enough to provide for their families. He had an older brother who was a Theyyam performer of some repute, but he drank too much, wasted all the money he made, and was of no use to anyone. Murali’s life was merely survival amongst these people.

Tailor Chindan had been an active member of the rationalist movement for over thirty years. At a very young age, he fell out with his uncle Kunjaraperuvannan, mainly because of the uncle’s cruel and volatile nature. But that did not stop him from falling for his uncle’s daughter, and their love grew day by day as they themselves grew older. Kunjaraperuvannan tried his hardest to break them up, but was unsuccessful.

The uncle was a respected leader of the Vannan communities in Chenkara and Theeyoor, a capable, sharp and eloquent man whom people did not confront directly. He was aware of his capabilities as well as his status within his community, so the disobedience shown by his daughter and his nephew was more than he could excuse. He tried various tricks to get back at his nephew, but nothing worked, and Chindan was undeterred. Moreover, his hatred and enmity towards his uncle became all-encompassing, and spread towards everything his uncle represented. Chindan challenged the age-old rituals and traditions treasured by his own community. He argued that the ritual of ‘Vannathi maattu’ – the traditional ‘right’ bestowed on women from the Vannan caste to wash clothes for the Thiyya and other communities – was an unquestionable example of the inhumanity of the upper castes and the subservience of the Vannan caste. He spoke openly about the need to dismantle the kaavu – sacred groves that were the abode of spirits and local deities – and the ritual art of Theyyam, for the betterment of the community. Perhaps because of the poison from his nephew’s relentless stings, Kunjaraperuvannan seemed to undergo a rapid change. He began losing his mind and his memory, and one day, near Pilathara, he was hit by a bus and died. His sworn enemy was no more, but Chindan continued on his path of rationalism and atheism.

He tried, single-handedly, to stop the ritual of cock sacrifice at Theeyoorkaavu, the fallout of which left him with enemies all across the land. There were some who supported him and argued that he was right, and they banded together to poke fun at customs and beliefs. They declared that astrology and sorcery were ways of conning people, and printed leaflets explaining the psychology behind rituals such as spirit possession and exorcism. One time, Chindan led a procession of about eight or ten people from the Theeyoor railway station to the Kasturba Memorial Library in Chenkara, shouting the slogan, ‘No caste, no religion, no god for us.’

A week after the procession, this group did something that horrified all the believers in Theeyoor.

&nb

sp; The beginning of the festival at the Vayalumkara temple is marked by a special ritual. On the first day of the festival, before sunrise, the Velichappad – the oracle of the temple – bathes in the temple pond, dresses in red silk and appears before the Goddess. Then, sword in hand, he runs all the way to Theeyoorkaavu making sure that he is not seen by anyone. He receives a garland of flowers from the priest of Theeyoorkaavu, and runs all the way back to Vayalumkara wearing the garland. On the sixteenth of Meenam in 1980, Chindan and his gang hid in a spot along the Velichappad’s way to Theeyoorkaavu. As he approached, they jumped out, shouting, from their hiding place. Shocked and scared out of his wits, the Velichappad ran away without completing the ritual. The incident created a massive uproar in the community and led to a police case. It also sealed Chindan’s reputation as someone to be reckoned with.

But the man who challenged everyone and everything, including the gods and the customs of the land, was ignored in his own home. In the early days of their marriage, his wife had been impressed with the risks he took and was proud of the way he stood up for his beliefs, but over a period of time she came to dislike his methods and actions. His children felt no affection for their father who spent all his time and his hard-earned money in pursuit of the rationalist movement’s aims and ideals. They focused their affection, instead, on their uncle, their mother’s brother, Ambuperuvannan. Murali’s older brother Balan lived with this uncle from a young age. During one Onam festival, Murali accompanied his uncle dressed as Vedan – the hunter – and went from house to house for the Vedankettu ritual. When he returned home, his heart brimming with pride and his pockets full of coins, Chindan beat the living daylights out of him. He rained abuse on his wife, his brother-in-law and his older son who had, by then, already attained fame for his rendition in Theyyam of the legendary character Kathivanoor Veeran. Murali spent the night crying on his mat, and after that incident he never went to his uncle. ‘Stop playing dress up and conning people out of their money,’ Chindan told him. ‘Focus on your studies and get a government job.’ Murali obeyed his father, albeit with a deep sense of loss and hurt. Over time, these feelings abated, and in their place, he began to feel a grudging admiration for his father and his principles, and he too began to think about how customs and traditions enabled the subjugation and oppression of his people. Still, a permanent sense of emptiness remained deep within him.

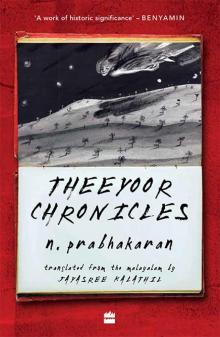

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles