- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

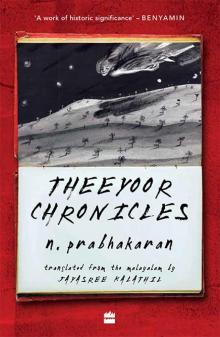

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 5

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 5

‘I haven’t written a single word about Indira Gandhi,’ he told Gopalan. ‘This is all my uncle’s doing. He’s determined to have me arrested.’

Gopalan had heard of the controversy surrounding Yakshikkalam. He was also aware of Chathu’s enmity with his nephew. From what Mohanan told him, the play seemed harmless. But Gopalan knew that if he got involved in this business, he would be in trouble. Chathu and his gang would turn their anger towards him, and there was no telling what they might do. However, the young man had sought his help. He sat silently, pondering the issue. He was on friendly terms with the sub-inspector, and a word from him could save Mohanan from further trouble and from jail. Mohanan was not a Naxalite or part of any extremist groups like the Rashtriya Swayamsevaka Sangham. There were a couple of Naxalites in Vayalumkara, and a few RSS supporters in Chenkara, but there were none like that in Thekkumbhagam. Mohanan was on friendly terms with a few Marxists, not because of any political allegiance, but because they tended to help him organize performances of his music and plays.

Gopalan could not come to a decision. In situations like these, Draupathiyamma would be the one to advise him, but it had been a while since he had sought her counsel. She had been keeping her distance ever since her relationship with Vijayan became strong, tiptoeing around Gopalan, and talking and behaving in an overly subdued manner as though she feared an explosion at any time. But Gopalan was determined to keep his calm. So many things had happened in his life, good and bad. There was nothing more that could happen to disturb his mental balance.

He was sixty-nine years old. Draupathiyamma was only forty-eight and looked even younger. Time seemed to have left barely a mark on her body, whereas he, while not entirely ancient, could feel that both his body and his mind were much less energetic than before. Although she had not mentioned it, Gopalan was aware that Draupathiyamma was affected by the depletion of his strength and vigour over the years. And then Vijayan had come into their lives, a young man but with the maturity of someone much older, and with the wherewithal to behave in a way that did not give any outsiders cause for suspicion. Gopalan had seen the effect of Vijayan’s presence on Draupathiyamma, the fresh blossoming of her body, the flitting smile on her lips, the renewed sparkle in her eyes … He did not think he had the right, like ordinary husbands, to be angry at her and to create a scene. After all, it was she who had taken him by his hand and brought him out of the pretentious world of spirituality and into the world of pleasures. Before meeting her, he had been fooling himself, pointlessly chasing after misconceptions. Now, he was unable to give her what she needed, and if she found it in someone else, he should be happy for her. Only then, he felt, could he truly say that he loved her.

As Gopalan sat submerged in these thoughts, Mohanan was feeling increasingly anxious.

‘Gopaletta, only you can save me,’ he said in a miserable voice.

‘You go ahead. I’ll talk to the inspector,’ Gopalan blurted out as he emerged from his reverie.

The next day, he went to see Sub-Inspector Balachandran.

‘Mohanan is one of our boys,’ he told the sub-inspector. ‘I don’t think the play will cause any problems.’

Balachandran had read the script, but was none the wiser for it as far as its content was concerned. All he had managed to do was underline in red some words such as ‘witch’, ‘bloodthirsty witch’, ‘witch’s army’ and so on.

‘As long as you can give me your assurance, Gopaletta,’ Balachandran said. ‘You know this is the type of case that can cost me my job.’

‘No, no. Nothing like that will happen,’ Gopalan assured him.

The play premiered on a stage specially erected in front of the public library in Thekkumbhagam. All the arrangements were made by Marxist Party supporters. No one in the audience understood what the play was about, but they all agreed on one thing – the ‘witch’ in the play had a clear facial resemblance to Indira Gandhi. Before the play could conclude, the stage was pelted with stones and mayhem ensued.

By the time the police arrived, everyone, including Mohanan, had run away. The only person remaining at the scene was the sound technician, and the police beat him within an inch of his life. The next day, the office of the Congress Party erupted in chaos as everyone shouted at once and called for Gopalan’s resignation. Without attempting to justify his position, Gopalan calmly agreed to their demand.

Draupathiyamma was furious that her husband had foolishly squandered his political future. But the incident had another unexpected fallout which upset her even more. Recognizing that Gopalan had fallen out of favour with almost everyone in the Congress Party and that he was now under the watchful eyes of the police, Vijayan cut off all ties with him. He was a shrewd young man, not about to risk his own future. He stopped his daily visits to their house and abruptly ended his dalliance with Draupathiyamma. With Vijayan gone, she felt she was losing her mind, and directed all her anger at Gopalan. He watched, astonished, the transformation of a woman’s loving heart into stone, the sudden change in its emotional season. Still, he remained at home, silent, stoic, seemingly unaffected by her wrath and hatred. And they continued to coexist under one roof, loveless, tasting nothing but the bitterness of life, until a new person entered their lives unexpectedly.

6.

Before Gopalan came into her life, Draupathiyamma’s only companion had been an old servant, Madhavi edathi. A widow from Chenkara, she had two children, both of whom had been married off before her husband’s death.

Madhavi edathi was of indeterminate age. She had a crumpled appearance, with a painfully thin body, a narrow face, and twig-like arms and legs, but she was almost unnaturally strong. She seemed unaffected by all the work she did and never voiced a complaint, as though the sole purpose of her existence on earth was to toil for others. She went home only during the festivals of Onam and Vishu, and stayed for no more than a day. On the first of every month, her daughter, Rohini, came to collect her salary. Her son, Divakaran, also came to visit her, but only rarely.

Draupathiyamma was very fond of Madhavi edathi. On the rare occasions when the old woman was not around, the kitchen fell into disarray, and the unfamiliarity of her own kitchen reminded Draupathiyamma of how dependent she had become on her. One day, after Gopalan had given up his position as the president of the local Congress Party and most of his other responsibilities, Divakaran arrived. Draupathiyamma and Gopalan assumed that he had come to visit his mother. In those days, discussions of public affairs that ensued between Gopalan and any visitors to their home irritated Draupathiyamma. When Divakaran and her husband began exchanging news and opinions about local politics and goings-on, she sat inside the house and muttered to herself, ‘Why does he sit there chit-chatting with that man? You’ve come to see your mother, so do that and get going.’ But when she overheard him reveal the real intention behind his visit, she stepped out on to the veranda.

Divakaran’s wife had just given birth to their third child. She had terrible back pain and was not able to do the household chores or look after the children and her father, an asthmatic, who lived with them. So they needed Madhavi edathi, and Divakaran had come to take his mother home.

There was nothing they could say, so all Draupathiyamma asked him was whether he might be able to bring someone else to take her place. Divakaran had very few connections locally. He was a man of all trades who travelled around doing odd jobs ranging from masonry to bakery work. He would work in a hotel for three months, then move on to trading foreign goods, buying them from Theeyoorians who had returned from the Gulf and selling them to folk up in the hills, or to a stint of brick work in Kasaragod. During the festival season, he would try his hand at selling sweets or doing circus tricks with an iron ball. For the last four months, he had been doing painting and decorating work under a foreman in Mananthavady and other places in Wayanad.

‘It’s difficult to find women who will come and stay with you,’ Divakaran said. ‘I could arrange for a young boy for the time

being. Won’t be of any use with kitchen work, but could help you with drawing water, washing clothes, running errands and such.’

‘Who is this boy?’

‘He’s from Wayanad. I might as well tell you the whole story. He’s an Adivasi boy, from the Paniya community. His mother had no husband, so not sure who the father is. He’s a good boy though, well behaved, you’ll see. The mother ate some poison fruit and died last month. He’s got no one now.’

Gopalan and Draupathiyamma were reluctant to take on the responsibility of having such a child in their home, but they were also desperate to have someone to help around the house. Finally, after much deliberation, they decided to meet with the child, have him around for a month, and then make a decision. Divakaran agreed, and a week later, on a Sunday, he came back with the child. The boy, Madhu, was only ten or eleven years old.

‘His original name was something else,’ Divakaran said. ‘His mother was obsessed with cinema and changed his name to that of her favourite star. Isn’t that right, boy?’

With wide inquisitive eyes, a beautiful smile, and thick, curly hair, Madhu was a striking child. Draupathiyamma could not imagine him as their servant. She got new clothes made for him, gave him a new name – Sunil – and called him by the loving epithet for son, ‘Mone’. Gopalan, too, found his pleasant behaviour and obvious intelligence endearing, and could not accept that he had been brought to them to do their household work.

‘Why don’t we get him educated?’ he asked Draupathiyamma.

‘We could, but he’s a bit too old, don’t you think? We can’t send him to class one.’

Gopalan went to a few teachers of his acquaintance, and heeding their advice, he decided to enrol him for class-four exams as a private-study student.

Sunil already knew the Malayalam alphabet. He had a keen memory, and picked up everything that Draupathiyamma and Gopalan taught him, in competition with each other, over the next several months. In March 1977, Sunil took the exam in Theeyoor Lower Primary School. Afterwards, the headmaster Kunjikannan maash told Gopalan, ‘He’s answered every single question. I was truly amazed looking at his answer sheet.’

Gopalan and Draupathiyamma went together to enrol Sunil in class five in Theeyoor High School. In the morning, Draupathiyamma took the boy to the temple. ‘Bhagavathi, bless my boy,’ she prayed with all her heart. ‘Don’t get involved with any unruly children,’ she told Sunil repeatedly. ‘Study hard and excel yourself.’

By 9 a.m., she was dressed and ready. ‘No need to hurry,’ she told Gopalan. ‘The inauspicious Rahukaalam will be over in a few minutes. We can leave then.’

At first, Sunil was intimidated by the big school with hundreds of children, but as time went by, he realized that he was better at his lessons than all his classmates. From then on, school became fun. After class five, Gopalan and Draupathiyamma did not have to intervene in his studies as he did his schoolwork diligently and on time, resolving never to leave his work undone even for a day.

A boy named Venu from Chenkara sat next to him in class. One day, Venu gave Sunil a book he had borrowed from Kasturba Memorial Library, P. Narendranath’s Andhagayakan. Sunil devoured the book, the first he had read outside of his schoolbooks, in one sitting, and was engulfed by an ocean of emotions that he had never experienced before. When alone, he was prone to descending into a dark cavern of sad memories. As he read the book, some of those memories surfaced, but there was something different about them this time. They were stronger and more intense, yet he experienced them differently. Was he beginning to realize, however faintly, the possibility of an existence outside of them? Or was it that he was beginning to find a different meaning, something that he had not considered so far, in the traumatic experiences he had already undergone at his tender age? Was he even, for the first time in his life, feeling proud that he had endured experiences that none of his peers had? But he did realize fully the desire and the sense of urgency to read many more books such as the one he had just finished.

The day after he returned Andhagayakan, Venu brought him an abridged translation of Oliver Twist. Sunil read the little book, a tattered copy with its covers and first few pages missing, and afterwards hugged it to his chest, where, like another heart, it beat in rhythm with his own.

The next day, with Draupathiyamma’s permission, Sunil went to Chenkara with Venu and took membership in the children’s section of Kasturba Memorial Library. Reading became an obsession he could barely control. Every day, after school, he gulped down his coffee and ran to Chenkara to the library. On holidays, he made two trips because, by evening, he would have finished reading the book he had checked out in the morning. Draupathiyamma grew to be concerned about his habit of shutting himself up in his room and reading.

‘Do you have to read all the time?’ she asked him. ‘Don’t you want to play with other children? It’s not good to sit in your room all day long.’

Sunil did not argue with her, but quietly continued his habit. He had no interest in going out or playing with other children. When she saw that he was reading storybooks instead of doing his classwork, Draupathiyamma admonished him, at one point losing her cool and scolding him. But Sunil was undeterred. He slipped away to Chenkara, brought back library books hidden inside his vest, stuck them in his schoolbooks and read them. Draupathiyamma found out eventually, and she blamed Gopalan.

‘You don’t say anything to him, that’s why,’ she said. ‘You wait and see, this is not going to end well.’

Gopalan did not give much weight to her concerns. ‘Sunil is an intelligent boy,’ he said. ‘I don’t think we need to interfere. Let him read whatever he wants.’

His reply irritated her and she fought with him, accusing him of not having Sunil’s best interests at heart. But soon, something happened that affected her deeply and destroyed her relationship with both Gopalan and Sunil.

It happened on the day Draupathiyamma took Sunil to the Vayalumkara temple festival to see a play. There, quite unexpectedly, she ran into Vijayan. It had been over three years since she had seen him, and suddenly there he was at the women’s side of the audience, pretending to repair a tube light. Seeing him standing right next to her, Draupathiyamma could not resist the urge to lift her hand and touch his shin. He turned around, and his face blanched as he looked at her. Trying to hide his disconcertion, he said, ‘Oh, it’s you! How are you? How’s Gopalettan?’ and left without waiting for a response.

By the time she got back home, Draupathiyamma felt like a swarm of hornets had taken up residence inside her head. That night, she picked a fight with Gopalan for no reason, and yelled and screamed at him. He tried his best to keep calm as he stood reeling, faced with the onslaught of her anger which showed no sign of abeyance even by midnight. At some point in the night, Sunil, who had fallen asleep tired after the play, woke up. As she rained abuses on Gopalan, Draupathiyamma became aware of Sunil’s eyes on her. He stood perfectly still, with a sly smile on his lips and an unblinking look that pierced right through her. Draupathiyamma felt that it was not the look of a child or of an ordinary older person. She felt exposed, and she was overwhelmed by an urge to run and hide, to disappear off the face of the earth. Exhausted, unable to face his scrutiny, she screwed her eyes shut.

7.

The night was unendurable. It was past 2 a.m. by the time they went to bed, and yet morning seemed a thousand nights away. Draupathiyamma could not sleep. Every time she managed to calm her uneasy wandering mind, the memory of Sunil’s gaze came back to her, and the sneer on his lips fell like burning sparks on her skin. When morning finally came, she found herself unable to look directly at him or call him ‘Mone, my son’ as usual.

Sunil realized that, overnight, the woman he had considered his mother had distanced herself from him, but he could not figure out why such a drastic change had taken place. All Draupathiyamma felt towards him now was a sense of dread mixed with anxiety. She was unable to examine why she was gripped with this feeling towards a child,

however mature he might be mentally, nor could she entertain the idea that she might have read unintended meanings into his look and smile. She had entered a mental state which made such rational thought impossible. Days passed by, but she could not displace this state of mind. She continued to cook his favourite meals, wash and iron his clothes, put his lunch money and change for the bus in his pocket. But beyond that, she withdrew from getting involved in his affairs. Her relationship with Gopalan also underwent a change. She stopped arguing with him. Although she knew she could not love him or touch his body marked by the ravages of time with eagerness, she went back to acting the part of the devoted wife, careful not to do or say anything that would hurt him. She took no pleasure in his company, and was unable to have a meaningful conversation with him. An uncomfortable silence descended upon the house, and three souls with nothing to share but unable to go their separate ways suffocated under its weight.

The sudden change in his wife’s behaviour baffled Gopalan. He could not figure out the reasons behind her seemingly endless silence or the obvious expression of vulnerability on her face. He was bothered by this change even as he found it safe. Ever since the incident with Mohanan’s play and his resignation as the president of the Theeyoor Mandal Congress Committee, she had barely said a nice word to him or spoken to him gently, her rancour mellowing only when they had to talk about Sunil. Such a woman had turned, almost overnight, into a docile, soft-spoken shadow of her former self, and he entertained the thought that she might have lost her mind’s balance. He was at a loss to make sense of this transformation, especially since it had happened after an entire night of fire and fury.

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles