- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 4

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 4

One day, when they were having coffee, they heard a commotion outside. Leaving Gopalan inside, Draupathiyamma went out to investigate and found Bhaskaran Nair, her dead husband’s younger brother, and a couple of young men in her front yard.

‘What do you want?’ she asked, her face expressionless.

‘We’re not here to see you,’ Bhaskaran Nair replied. ‘Where’s that lying swami? Send him out.’

‘There’s no one like that here.’

‘So who’s that inside?’

‘My husband.’

‘Your husband! Thoo…’ Bhaskaran Nair spat on the ground. ‘When did he become your husband? This house and land – all of this belongs to my brother. I won’t let that tramp come and go as he pleases.’

‘Who the hell do you think you are to have an opinion?’ Draupathiyamma shouted. ‘Your brother is dead. This property is in my name and I’ll decide who should come in here, including you and your goons.’

Defeated by her fiery attitude, they soon withdrew. ‘We’ll show you, you hussy,’ they said as they left. ‘See if we don’t put a stop to your whoring.’

That night, the house was pelted with stones, and there were shouts and booing from the lane. It continued for a few nights and then gradually stopped. Draupathiyamma, meanwhile, was in the process of transforming Gopalan. She got rid of his ugly clothes, and instead, dressed him in a khaddar mundu and a short-sleeved shirt made of high-quality milled khaddar. With a pair of expensive Kanpur sandals on his feet, a Favre-Leuba wristwatch and a gold chain around his neck, Gopalan was a changed person.

When his hair and beard grew long, she sent him to the barbershop, and when he returned, she declared that his moustache wasn’t quite right and trimmed it herself. She tended to him as though he were a small child, anticipating all his needs. When in the company of others, she played the role of a docile and obedient wife, one who asked his permission for everything, and spent not a paisa without his say-so. But in the privacy of their bedroom, she revealed her true self, transforming into a cascade of desire that swept Gopalan away in the rushing waters of sensual pleasures. She was, in some ways, getting back at her dead husband.

In Singapore, Ananthan Nair had been a clerk in a film distribution company named Paulsons, and had owned, in partnership with a friend, a printing company that produced picture postcards. He also had some other secret dealings. Ananthan Nair pursued an unfettered life focused only on his own welfare and happiness. Before he married Draupathiyamma, he had three mistresses, two Tamil and one Chinese, and when he brought Draupathiyamma to Singapore, he did not end those relationships or stop his nightly visits to the dance bars of Jalan Besar. Draupathiyamma came to hate her husband who showed no interest in her and only used her to gratify his bodily pleasures, and her own body’s betrayal in responding to his expert lovemaking despite her hatred depressed her.

She was not allowed to ask questions about the Chinese friends who came to visit him at odd hours or about their secret dealings. He had made it clear right from the start that all she needed to know was that he was working hard to make money for her. He had a loud voice that hit one like a slap in the face, and Draupathiyamma was scared to entertain questions even in her mind. All she knew was that he was involved in various moneymaking schemes. And one morning, when he suddenly collapsed in their bedroom and died, Draupathiyamma burst out crying uncontrollably, not out of love for him, but from the realization that, in that moment, her married life had come to an unceremonious end. The realization destroyed her inner strength, and as though possessed by an evil spirit, she forgot herself.

On the day he died, it was almost 4 a.m. when Ananthan Nair had come home in a car with two of his Tamil friends. He was so drunk that his friends had struggled to carry him inside. And they left immediately, without saying a word to Draupathiyamma. Ananthan Nair was barely conscious, but that did not stop him from pouncing on her, and with a lecherous laugh, attacking and subduing her. It had been almost a month since he had spent a night with her, and as though to make up for it, he drowned her in the ocean of his desire.

Draupathiyamma woke up at around 9 a.m., emerging from her sleep as though from the bottom of a deep sea. Panicking at the lateness of the hour, she scrambled up and shook her husband who was snoring next to her. As he got up from the bed with a hollow look in his eyes, he pressed a hand to his chest and fell to the floor, groaning.

Afterwards, the stories that spread about the death that had happened in front of her eyes hurt Draupathiyamma deeply. People said that she had been familiar with the two Tamilians who had brought her husband home, and that they had colluded in killing him by giving him brandy laced with poison. Gradually, this bizarre story began to seem real to her, and she found herself unable to shake this thought even after months had passed and she had left Singapore and returned home to Vayalumkara. It was when she could not banish this thought from her mind, despite repeatedly trying to convince and admonish herself, that she started seeking solace at the Vayalumkara temple. Still, a vague uncertainty remained like a damp cloak over her mind, but it began to dissipate from the moment she met Gopalan.

What Draupathiyamma saw in Gopalan was a completely different man from Ananthan Nair. His appearance, demeanour, gestures were all different from her late husband’s, and he had a brightness of face and a gravity of voice that were reflective of his thoughts, erudition and simple way of life. She found it captivating. When she saw him for the first time on the first day of his lectures, she could not look away from him, and for the next thirteen days, she was in a daze as her eyes drank in his image. Her desire to have this man beside her for the rest of her life took on an intense meditative quality, and she knew from the way he looked at her for the first time that she would not be disappointed.

And so, when Wardha Gopalan arrived at her front door, depleted of his self-belief and courage, Draupathiyamma was the happiest woman on earth. From that day on, her life’s primary purpose was his well-being. His successes gave her great pleasure, and each slight he endured cut her to the quick.

Draupathiyamma enjoyed appearing in public with Gopalan. Dressed in their finery, they went to watch movies at Olympia Talkies in Theeyoor Kunnumpuram, an area on top of a hill, and strolled in the gentle breeze along the banks of Vayalumkara River in the evenings. Draupathiyamma did not dwell on the twenty-odd-year age difference between them. It was a concern only for other people. In the beginning, as they passed by laughing and chatting with each other, their bodies touching, young men found great merriment in ogling and whistling at them and making indecent comments. Older people, too, were not reluctant to make snide remarks: ‘What sort of people are these?’ and ‘There’s no limit to their shamelessness!’ These comments made Gopalan hang his head in embarrassment, but Draupathiyamma was undaunted. She wanted to prove that the two of them were happier than everyone else, and was convinced that all the comments and catcalls would soon come to an end.

Ananthan Nair, at the time of his death, had considerable savings, which Draupathiyamma had deposited in the bank along with the money she received from Paulsons after his death. The interest from this and the income from her five-acre fields provided enough money to live comfortably. Many of the neighbours had experienced her generosity, and although they disapproved of her relationship with Gopalan, they still came to her in times of need. Only some arrogant rich households and some prominent people associated with the temple shunned her completely, and continued bad-mouthing them, calling Draupathiyamma licentious and Gopalan a scrounger. But most people did not care beyond a point, and as time went by, even the ones who had previously been unsure and kept their distance renewed their associations with Draupathiyamma. Soon, representatives of cultural associations, school committees, reading rooms and so on started dropping in, hoping for donations. Draupathiyamma instructed Gopalan to speak with all of them and do what was needed. She wanted to impress upon her countryfolk that it was Gopalan who was in charge of all her wealth.

When the young Congress Party supporters had come to him wanting to rent the room, Sraap had agreed, but on two conditions: one, Wardha Gopalan himself should come and ask for it, and two, six months’ rent – ninety rupees – should be given in advance.

Gopalan had cut all ties with the Congress, and not wanting to get involved in their affairs again, had resolved to send the young men off with a donation of five or ten rupees. But when he went in to get the money, Draupathiyamma took him aside.

‘Don’t do that,’ she advised. ‘You must go to Sraap and ask for the room. And give him the ninety rupees advance yourself. It will be to our advantage if we have the Congress Party on our side.’

5.

Draupathiyamma was not the kind of person who took decisions or made remarks without thinking them through. She had some concrete plans for Gopalan’s future, and she made sure that their lives progressed according to these plans.

When it was time for the opening of the National Arts and Sports Club, Theeyoor, the organizers invited Gopalan to inaugurate it. After the function and the reception that followed, Gopalan decided to visit Devu edathi before returning to Vayalumkara. He had not quite had the courage to see her ever since he had taken up with Draupathiyamma. She would not hate him, he knew, but it was possible that she would be displeased. Still, how long could he avoid her? There were still some people who turned away or gossiped about him behind his back, but no one shunned him any more. He was now Draupathiyamma’s husband for all practical purposes, even though they had not formalized the relationship. And he had become quite well-off thanks to his wife’s wealth, which had given him some recognition in the community. A couple of ill-wishers were not going to take that away from him. After all, people respected wealth, everything else was immaterial. Devu edathi was not someone who put much value in someone’s financial circumstances, and he was certain that she would not begrudge him a good life.

Resolving to leave without regret in case Devu edathi was less than welcoming, Gopalan climbed the steps to the veranda. His unexpected arrival brought tears to her eyes, and brother and sister stood there for a while, struggling with their emotions. She insisted that he have lunch with her, and as he left after eating, she said to him, ‘Next time, bring her too. I haven’t met her yet.’

Gopalan returned to Vayalumkara invigorated by the reconciliation with his sister. He told Draupathiyamma all about the inauguration and the visit with his sister. From then on, Gopalan began to get involved in public affairs with self-confidence, seeking Draupathiyamma’s counsel in each new venture, and she provided it with great care and discernment. She was not conversant in political matters, but had intuitively identified the Congress Party as a place where Gopalan could thrive. She also believed firmly that, Congress or communist, they had to play their hand carefully and cunningly if they were to make progress.

Within a brief period, Gopalan became one of the prominent public figures in Theeyoor, Vayalumkara and Chenkara. He took on various public responsibilities – the president of the Theeyoor High School Development Association, the treasurer of the Chenkara Shiva Temple Renovation Committee, the director of the board of Vayalumkara Service Cooperative Bank. The upper-caste folk who had shunned him when, over twelve years ago, he had tried to involve himself in the affairs of the Congress Party, were cowed by his current prestige and popularity. And Chathu, the leader of the Congress in Theeyoor Thekkumbhagam, attached himself to Gopalan, calling him Gopaletta even though Gopalan was a couple of years younger than him. When Ambu Nambiar, the president of the Congress Party in Theeyoor mandal, or subdistrict, passed away, the members unanimously elected Gopalan to the post. On the same evening, Chathu organized an alcohol prohibition meeting in Thekkumbhagam and took Gopalan to address the audience.

In 1969, the Congress Party split in two. Gopalan’s inclination was to side with the faction that went against Indira Gandhi. But Draupathiyamma was cautious. ‘Don’t say anything yet,’ she told him. ‘Let’s see how the pieces fall and which side emerges stronger.’ Despite wavering at first, Gopalan eventually stood with the Congress (I), the faction supporting Indira Gandhi. Most of the old league in Theeyoor joined the opposing side, and for a brief period, it looked as though they might be on the ascendant.

It was not until 1975 that there was another crisis in Gopalan’s political life, and this time, the issue was not confined to politics. Ambu Nambiar, the previous mandal president of the Congress Party, had a grandson named Vijayan, an energetic, seventeen- or eighteen-year-old young man often dressed in a pure white khaddar mundu. Gopalan took a special liking to him and brought him home on several occasions. Normally, Draupathiyamma did not approve of inviting people home and entertaining them, but she made an exception in Vijayan’s case.

In the eleven years she had spent with Ananthan Nair and in almost as many years with Gopalan, Draupathiyamma had not been able to conceive a child. Gopalan had taken her to all the local healers, as well as to the expert doctors in Mangalapuram. Nothing worked, and they had, with great sorrow, resigned themselves to a life without progeny. When she first met Vijayan, what Draupathiyamma felt towards him was a mother’s tenderness, but he, it soon became clear, nursed within him a strong sexual desire for her. The realization shocked her at first, and she wept bitterly. However, she did not tell Gopalan about his intentions, and soon began looking forward to and enjoying Vijayan’s attention.

Before long, Gopalan became aware that things were not as they seemed. The changes in Draupathiyamma’s behaviour, and the excessive freedom with which Vijayan conducted himself around the house roused his suspicions. Finally, his suspicions were proven beyond any doubt when he caught them together in his own bedroom.

That was on the night of 20 June 1975, but later, Gopalan would always remember it as the night of the twenty-fifth.

On 25 June 1975, a few minutes before midnight, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared emergency rule. Gopalan was appalled. He tried his best to understand this decision, but he could not come to terms with it. He criticized the decision openly and without consulting Draupathiyamma as usual. Several members of the local committee, especially those who still secretly nurtured resentment and jealousy towards him, were upset, and they reported him to the district committee of the Party. A leader of the district committee arrived and had a night-long conversation with Gopalan.

The leader had nothing much to say about the declaration of the Emergency or the twenty-point economic action plan that the prime minister had announced. Instead, he warned Gopalan repeatedly that there were several leeches waiting to suck his blood in the Party’s committee in Theeyoor mandal and in the District Congress Committee, and that he should be careful not to create situations detrimental to his own interests. Gopalan understood one thing very clearly: that it was dangerous to voice critical views. He realized that if he lost his position as the president of the local committee, it would be the end of his political life. No one who opposed the Emergency would be accepted as a member of the Congress Party, no matter how much they proclaimed their allegiance.

‘Gopaletta, you’ve been involved with the Party since the time of Mahatma Gandhi,’ the leader told him. ‘But that will mean nothing to the youngsters today. Best if you don’t rock the boat. Keep silent. It’s for your own good.�

�

He was right, Gopalan realized, and kept his own counsel. He continued in the Party, humble, obedient and silent, until January 1976 when he got himself into some serious trouble.

Chathu, the Congress activist from Theeyoor Thekkumbhagam, had a nephew by the name of Mohanan, an accomplished singer and actor, and a sworn enemy of his uncle. Mohanan had written a play titled Yakshikkalam – Witch’s Warfield – and when the rehearsal of the play began at the public library, there was talk that the ‘witch’ in the play was Indira Gandhi. Chathu personally went to Theeyoor police station and filed a complaint. The sub-inspector of Theeyoor station, in those days, was a young man from Payyannur named Balachandran. He ordered Mohanan to submit a full copy of the script for inspection. A terrified Mohanan took the script to the station within the hour.

‘Come back tomorrow,’ the sub-inspector said. ‘I’ll pass this on to the circle inspector. We’ll decide whether or not this should be performed.’

By the time Mohanan came back from the station, a false story, instigated mainly by Chathu, that Mohanan had been arrested, had spread across Theeyoor. It had never occurred to Mohanan that he would get entangled in such a controversy when he was writing the play and rehearsing it. He was just an ordinary man, fired up by youthful enthusiasm, with a tendency to be contrary and a desire to stand up to injustice, but without the courage or the political conviction to back it up. The fate of his play stunned him, and he was terrified of the possibility of being arrested. In a matter of hours, he had become an outcast, shunned even by his closest friends. Someone advised him to go see Gopalan, and he went and told him all that had happened.

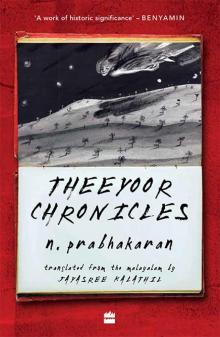

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles