- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 15

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 15

As I climbed up the stairs, holding on to a rope that served as a banister, I heard someone sing from the room upstairs:

Here, where Nabi the Noble was born

Here, where the Qur’an was completed

Here, where histories slumber in peace

Here, the beacon shines for all to see

Alternative Narrative

‘Amu is all right, but he’s also a con artist. Like most folk, I reckon.’

Beeranikka sat leaning against a boat pulled up on to the beach. He was an entertaining storyteller, as we would soon find out. That evening, Ravi and I sat there listening to him for hours.

Almost twenty-four years ago, when Amu Jinn arrived on Theeyoor beach dressed in tatters and with a dirty bundle over his shoulder, he looked every bit like a homeless madman, Beeranikka told us. Still, he took him home, got his wife to boil some water for his bath, gave him a set of clean clothes, and fed him. He could see that the friend he had run into several months ago at the courthouse had undergone some kind of transformation, but he had no idea what had caused it. Amu Jinn refused to answer his questions no matter how hard he pressed, and what he did say made no sense to Beeranikka.

At that time, Beeranikka’s nephew Jamal, who had been working in a chai shop in Ettikulam, had returned home, listless and in a muddled state of mind. He began showing peculiar behaviours such as standing motionless, like a distressed chicken, in a corner of the room for hours. He stopped eating regularly, bathing, or praying. The sudden change in the strapping eighteen-year-old lad troubled Beeranikka much more than it did his own parents, and when a friendship began to develop between Jamal and Amu Jinn, no one was happier.

One day, Amu Jinn made Jamal sit on a low stool in the yard. He poured a bucket of water over his head, and proceeded to beat him, very gently, with a switch he had broken off from a nochil shrub, all the while murmuring something in a voice so low that no one could make out what he was saying. When the beating was over, he scrambled up a coconut tree in the front yard and cut down a tender coconut. He opened his bundle, took out some powder and crumbled leaves, mixed them in the water of the coconut, and made Jamal drink it. Amu Jinn dried Jamal’s hair with a towel, and by then the young man was sleepy.

‘There’s nothing to worry about,’ Amu Jinn told the family. ‘Take him inside and let him sleep. He’ll be all right.’

Amu Jinn left. All this had taken place at around half past eight in the morning. Jamal slept, uninterrupted, until it was time for the Asr, the afternoon prayer. And as he slept, his deeply troubled parents and Beeranikka kept an anxious watch.

When Amu Jinn came back home, it was after sunset, and Jamal was sitting on the broad veranda skirting the house, enjoying a meal of pathiri and meat curry. The long sleep seemed to have fixed his listlessness and dejection. Within the next couple of weeks, Jamal found a job by his own initiative, selling tickets in a newly opened movie theatre on Beach Road.

News about Amu Jinn’s miraculous cure of Jamal’s illness spread far and wide, and very soon people began to come seeking his help in all manner of problems – robberies, spirit possessions, madness, chronic illnesses … ‘There was a lot of trickery and sleight of hand,’ Beeranikka said, ‘but his heart was in the right place and people believed in his abilities.’

A corner of the veranda in Beeranikka’s house was partitioned off with a cloth screen, and Amu Jinn met his clients in this enclosure. He did not allow meetings on Fridays, which he spent alone, praying. On other days, a veritable ocean of people surged in Beeranikka’s front yard, hoping for an audience with Amu Jinn, and a local lad set up a kiosk just to sell beedis, cigarettes and sherbet to them.

In a couple of years, Amu Jinn made quite a bit of money, but he was careless with it. He was also always ready to help others, lending them ten or twenty rupees just for the asking. Jamal himself began taking advantage of him. Finally, Beeranikka persuaded him to buy a twenty-cent plot near Valiya Palli, build a small house on it, and bring his wife and children to live with him.

There was a young man named Shukkur in the locality. He was from a well-to-do family, and looked the part too, but he was a thief. Shukkur had begun his thieving ways at a young age, first stealing from his own family before proceeding to steal watches, timepieces and other such items from the houses of his relatives and family friends. When he was older, he left home and went to Bangalore and Madras where he became a pickpocket. He would come back home every four or five months, dressed in hats and sunglasses and carrying expensive-looking suitcases. For the next few weeks, he and his friends would be seen having a good time at the cinema, or picking tender coconuts off trees, or drinking. So when Amu Jinn decided to get his daughter married to Shukkur, Beeranikka tried his best to persuade him otherwise, but Jinn disregarded his advice.

The marriage took place, and Shukkur went away on the sixth day after the wedding. His next visit was two months later. He looked like an affluent man returning from Dubai, and he brought with him a lot of things that were unavailable locally, as well as gold and money. Amu Jinn’s wife and daughter were duly impressed. Before he went back again, he helped his wife’s younger brother set up a small shop next to the railway station. On his next return, he did not bring anything of value. But he had a gift for Amu Jinn – a pair of binoculars. Shukkur was not the kind of person who would consider whether such a gift was of any use to a person like Amu Jinn. In any case, Amu Jinn was only too happy to accept it with grace.

On this visit, Shukkur was home for almost a month. Then he left, saying he had urgent business in Bombay. A month and a half after that, two policemen from Tamil Nadu came to the Theeyoor police station. They were looking for Shukkur, who had robbed a house in Coimbatore and made away with thirty pavans worth of gold and 5,000 rupees. Accompanied by the Theeyoor police sub-inspector and two local policemen, they came to Amu Jinn’s house and questioned him and his family. Everyone heard what had happened, and after the police jeep left, a crowd milled around outside the property. For the next several days, Shukkur was the main subject of discussions around the Theeyoor beach area, but no one had any fresh news about him.

A couple of weeks later, a man named Ummar came to see Amu Jinn. He was from Kadumeni, a place quite far away from Theeyoor. He had come to see Jinn on a couple of occasions before, and was also acquainted with Shukkur. Ummar had been to the festival of Vayanattu Kulavan Daivamkettu in a place near Kanjangad. He told Amu Jinn, ‘I saw him there – Shukkur – just yesterday, with my own two eyes.’ He was standing near the Kanjangad bus stand, Ummar explained, when a car had pulled up by the side of the road, and a man in a suit had gotten out with a woman dressed in a shirt and trousers. Ummar recognized the man, and called out, ‘Shukkur!’ The man turned and looked, and hurriedly pushed the woman back into the car and drove away.

The only person Amu Jinn shared Ummar’s story with was Beeranikka, and Beeranikka advised him to keep it to himself. Shukkur had not returned since.

When the police came to question Amu Jinn and his family about Shukkur, his daughter had been four months pregnant. She held on until she gave birth, but afterwards the stress of the situation overcame her, and her mental state deteriorated. She withdrew into herself, stopped talking, and eventually started doing weird things like removing all her clothes and running out of the house. Amu Jinn tried his best, but he could not find a cure for his own daughter. His failure affected him deeply, and he began to behave erratically. He became abrupt and disrespectful towards his clients, and a lot of his predictions and advice began to backfire. The tide of his fortune ebbed as quickly as it had risen, and within a very short period of time, Amu Jinn became unwanted.

It was then that Amu Jinn found a use for the binoculars Shukkur had given him. He became a permanent fixture on the beach at sunset, watching the sea through his binoculars until late into the night, sometimes even after midnight. What visions did he see in the endless expanse of the ocean? No one could figure this out as they watc

hed the man watching the sea, sometimes with tears flowing down his cheeks and sometimes laughing out loudly. Youngsters made fun of him. ‘What now, Amukka, can you see the angels in heaven? Can you see God Himself?’ they would ask. Amu Jinn paid no attention to them.

Those were days when he earned nothing. His household survived on what he had saved up earlier in the good days. His older son’s business yielded nothing much in profit, and his younger son was too young to help out. Two or three years later, things began to deteriorate further. Resources for daily survival became hard to find. His daughter, still mentally frail, began to develop physical health problems such as asthma and rheumatism. None of this put an end to Amu Jinn’s evening meditations on the beach, binoculars in hand.

One evening, a man named Hassankutty Haji went up to him. ‘Listen here, Amu! Could you do us a favour?’ he asked, mostly as a joke. ‘We seem to have misplaced a gold necklace weighing three and a half pavans. Could you help me find it?’

Amu Jinn placed his binoculars on the ground. He then gave Hassankutty Haji a stern look, and drew a rectangular, box-like shape in the sand.

Haji went home and looked in all the boxes, big and small, he could find. The lost gold necklace was not to be seen. Feeling ridiculous for having taken a mentally unhinged man’s suggestion seriously, he sat in a room leaning against a wall, dejected. That is when he spotted, amidst a pile of old clothes in a corner of the room, the ‘instrument box’ – a rectangular metal box containing set squares, a ruler, a compass and so on – belonging to his son who was studying in class ten. A shockwave passed through Hassankutty Haji’s heart. The boy had been keeping questionable company of late. Haji had suspected that it was him behind the occasional disappearance of money – 100 rupees here, 200 there – from the drawers of his table. When the necklace went missing, it was the boy Haji had thought of first. There was no point in confronting him, so Haji had taken to watching his comings and goings surreptitiously. Haji believed that there were some jumped-up women in the market who were really responsible for turning Shukkur into a thief, and if the boy had fallen into their bosoms, there would be no telling what he would do. Besides, having spent two years instead of one in classes five and six, the boy was already eighteen – an age when the blood ran hot and swift in the veins – and looked like a fully grown man. So it was with the firm belief that the necklace would be inside the instrument box that Haji opened it. And there it was, just as Amu Jinn had predicted! Hassankutty Haji felt a deep admiration and respect for the man, and told all and sundry about the ‘miracle’ that he had just experienced.

No one was certain how or why it happened, but Amu Jinn’s luck took another turn. His daughter seemed to recover her mental peace, and began returning to her usual self. This seemed to bring about a change in Jinn’s behaviour, and he resumed behaving courteously to others. It was at this time that a strange incident that would reaffirm people’s belief in Amu Jinn’s mystical abilities occurred. A man named Moideen, who worked in a rice shop in Theeyoorangadi, had gone to the top of Theevappara one afternoon. There, on the deserted expanse of the rock, something scared him so deeply that when he came down the hill, all he could do was hiccup continuously. Dr Hameed in Theeyoorangadi who examined him said to his relatives, ‘He’s had a mental shock. There’s a doctor in Kannur. I’ll give you a reference letter. Take him there.’ As the relatives got ready to take him to Kannur, someone suggested taking him to Amu Jinn first.

Amu Jinn took Moideen inside his house. He held Moideen’s nose shut while chanting something. Then he made him drink a mouthful of water, and hit him hard on his back. It was all over in a couple of minutes. The relatives looked on astounded as Moideen came out of the house smiling, his hiccups gone. The incident sealed people’s faith in Amu Jinn’s abilities.

However, Amu Jinn did not continue living in the beach area of Theeyoor for long after that. He began to believe that the land he had bought near Valiya Palli, where he had built his house, had something wrong with it. And when people began to consult him again and his prospects improved, he bought a small plot of land below Theeyoor Kunnumpuram, and within the next three years, built a house there. He sold his old land and house and moved into the new one with his family, and from then on his luck got better and better.

‘But still, in the end what happened? Lost everything, didn’t he?’ Beeranikka said, bringing the story to a close. ‘The games God plays … The itty-bitty games we play on this earth are no match for His.’

He sat quietly for a while as though listening carefully to the roar of the waves.

‘The games God plays…’ he repeated, as we walked away from the beach. ‘What all have we heard, witnessed, and yet who knows what awaits any of us! Take Ramachandran, for example, Appanu Nambiar’s son. Who was he at one stage? Had the whole land genuflecting in front of him, didn’t he? And then…? Took two days for his body to be discovered after he hanged himself.’

The roaring wind tore Beeranikka’s voice into tatters.

HE WHO LIVED BY THE SWORD

1.

On 3 April 1942, the Japanese bombed the city of Mandalay in Burma. Among those who were able to escape, as the city burned to the ground, were some Theeyoorians – Valiyaveettil Dakshayaniyamma, her husband Damodaran Nambiar, and their four-year-old son Appanu. But death was not done with them. The family endured untold suffering and finally managed to reach the refugee camp in Tamu, a town close to the Indian border. There, Damodaran Nambiar and Dakshayaniyamma succumbed to the cholera outbreak, leaving Appanu an orphan. It was a man named Kannan Menon, a native of Kodungallur, who brought Appanu to Theeyoor a month or so later.

Dakshayaniyamma’s mother and one of her older sisters were the only people at home on that day, and they received Appanu as though they were accepting an unexpected gift. They wept for his poor parents and their terrible fate.

In those days, Valiyaveettil was the richest landowning family in Theeyoor. But their menfolk were in other lands working in a range of professions, and there were none left back home to look after the landholdings. Subsequently, as time passed, much of the property was lost. Still, when he came of age, Appanu received two and a half acres of paddy fields as his share of the property, as well as the old ancestral house, a dilapidated structure that barely let in air or light, which none of the other relatives wanted. Appanu Nambiar had completed a teacher training course, and with a gift of 125 rupees to the manager of Theeyoor Lower Primary School, had acquired a job as a teacher. It was only when his grandmother passed away, leaving him completely alone, and when the subsequent partition of the family estate made him the owner of a house and some land that he finally thought about having a family of his own. In due course, at the age of twenty-seven, Appanu Nambiar married Sulochana, a beautiful young woman from a well-to-do family in Chenkara. The first six or seven years of their married life were heavenly.

The cause for the ultimate destruction of this peaceful and happy marriage was Sulochana’s older brother’s wife, Prema. Prema came to visit her sister-in-law regularly. She had an intense, almost pathological, need for love and sex, and her attractive smile and lustful body language soon caused Appanu Nambiar’s heart to wander. By the time Sulochana noticed, their relationship had moved on beyond the feeling of mutual attraction.

Sulochana’s initial reaction was a sense of helplessness, but soon she began to smoulder with rage and hatred. She looked for ways to hurt and infuriate Appanu Nambiar, but all her blistering words drowned in the river of desire for Prema’s body in which he frolicked. Sulochana was left with only one choice, and she turned her anger and hatred on to their only child, Ramachandran. In her state of mind, she did not think about the cruelty in behaving heartlessly towards a four-year-old child. She beat him for no reason at all, scolded him constantly, and found ways to stop him from doing anything that might bring him some level of joy.

In time, the constant volatile situation affected Sulochana’s mental state. She found several ways

in which to express her anger and frustration. On days when Appanu Nambiar came home late, she rolled up his mattress and left it in the front of the house. She spilled tea all over his teaching notes, put too much indigo in the water in which his clothes were washed so that they turned murky blue and unusable … Initially, Appanu Nambiar barely paid attention, but there came a time when he could no longer ignore her actions. He began arguing with her, and then laying hands on her violently which only egged her on. The person who suffered the most in this vicious circle was Ramachandran. His parents’ raised voices sent him into spasms of terror, and when they began fisticuffs, he wailed loudly.

Meanwhile, the intense desire Appanu Nambiar felt for Prema had begun to mellow, and with it, he began to feel an extreme mental and physical exhaustion. Even the slightest infraction now provoked him, and violence became a daily occurrence in that household. Growing up in this relentless atmosphere of altercations and animosity, Ramachandran too lost his sensitivity and developed a heart of stone.

Ramachandran did not have many friends, but by the time he got to high school and joined the Students’ Federation of India, the student wing of the Marxist Party, his days began to be filled with protest marches, sticking political propaganda posters, funds collection and so on. He had given up on his schoolbooks a long time ago, and did not take his school-leaving exams. Appanu Nambiar, who had tried to behave with gentleness towards him until then, was enraged, and father and son became sworn enemies.

Finding life at home unbearable, Ramachandran spent as much time as he possibly could outside. The office of a local sports club named Theeyoor Brothers was a room on top of a row of shops in Theeyoor Meleyangadi, the upper market area. The main activities of the club members were card games, carrom and endless gossip. Ramachandran took to spending most of his time there, and in the office of the Marxist Party in a room two doors down from the club.

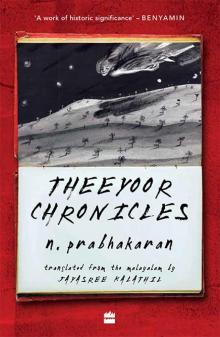

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles