- Home

- N. Prabhakaran

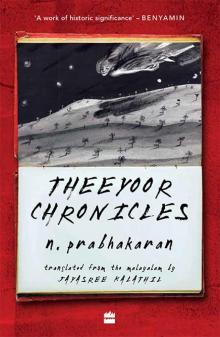

Theeyoor Chronicles Page 14

Theeyoor Chronicles Read online

Page 14

One Friday night, I got out of my home, and found myself in the maqbara of the mosque the rioters had destroyed with their stones. I felt unbalanced, out of control, and in that state I said out loud, ‘If there’s any powerful being here, if there’s a jinn here, show yourself. If not, I want to die right now.’ I began reciting the Yaseen, and suddenly, I heard a voice.

‘As-salamu ‘alaykum, ya habib.’

Oh, the shock! My mouth was dry, and I couldn’t finish the Yaseen. I saw an eerie red light, and emerging from it was a man with a green shawl around his shoulders, a milk-coloured wart at the edge of his narrow face, a grey beard, a long gown and a stick around two yards long in his hand. As this vision became clearer, I greeted him:

‘As-salamu ‘alaykum.’

‘Wa ‘alaykum as-salam,’ he returned my greeting. Then he said, ‘Amu, there’s nothing to fear.’

I didn’t hear anything else the man said. I don’t think I was conscious for the next half hour. When I opened my eyes, I was lying on the bare earth. I was alone. Slowly, I got to my feet. There was a well at the northern corner of the mosque, with a leaky-bottomed bucket tied to a length of rope. Shivering, I lowered the bucket into the well, pulled it up, and greedily drank the little water I had drawn. I don’t think I had all my faculties intact when I went back home that night.

The next morning, an old acquaintance of mine came to see me. A new hotel was opening up in Thalassery, he said, and I could have a job in the kitchen if I wanted. I accepted, and it was there that I learned to cook biriyani. In the initial days, I worked under the supervision of another man, and when he left, making biriyani at the hotel became my responsibility.

I had never made biriyani before, but it seemed that I had a special knack for it. Slowly, my biriyani became famous, and people began to come to the hotel just to eat it. That’s how I became known as Biriyani Amu. But this success was to be short-lived. I couldn’t work in that hotel for long. Politically motivated attacks and murders continued around Thalassery and neighbouring places. One day, I was standing in front of the hospital in Thalassery when a man was brought in a jeep with knife wounds to his head and chest. People gathered around to have a look, and so did I. One of the men who got out of the jeep was Kunjappa. He looked straight at me, and something in his look frightened me to the core.

I quit my job at the hotel and went back home. Even the thought of Thalassery town sent shivers of fear down my spine that confined me to my house. My wife was about to give birth to our third child. I was in a real state, what with the anxiety about the imminent birth, money worries, as well as the terror that clawed at my innards. I could only sleep for about two or three hours at night, and I had lost all interest in food. All I desired was water and a few tender betel leaves. I neglected changing my clothes, and barely interacted with my wife and children, and slowly they began to feel scared of coming near me.

My wife was due to deliver our baby any day now when the date for my appearance in court in relation to the case about the destruction of the mosque came around. I spent the night praying, calling out, ‘Ya Shaikh Muhyiddin!’ After a while, I felt my limbs go numb, my body lift itself into the air, and my memory fade. My wife told me later that when she tried to speak to me, I greeted her as though she were a stranger. She was terrified, she said, and that’s when she called the neighbours. I told them in great detail about the court case and my part in it. I don’t remember any of this. Anyway, the next morning I went to the courthouse, and nothing happened as I had feared. The hearing was postponed.

At the courthouse, I met my old friend Beeran. He had left the job in Mangalapuram, and had come back home and started a small business. He had come to see a lawyer in relation to a dispute around some family property. He asked how I was doing, and I told him all about my present situation.

‘Why don’t you come to my place?’ he asked me. ‘This land is no good for you.’

I knew Beeran was sincere when he invited me to move to Theeyoor, but at that point, I didn’t take it seriously. What difference would it make where I lived? The suffering would be the same, I thought.

Our troubles only increased after my wife gave birth. People stopped lending me money, perhaps they thought I’d become mentally unstable. My sister had been working as a kitchen help in a house nearby for a while now, and my nephew did occasional work as an electrician’s assistant. The entire household survived on what they earned. The situation was not ideal, and my sister would occasionally say something hurtful about it, which would annoy my wife who’d then respond, and soon we’d have a full-fledged war of words. My sister’s tongue was vicious. And when my wife would have had enough, she’d produce this loud howl five or six times as though possessed by a shaitan.

My oldest daughter was twelve. She’d stopped going to school after failing in class three. One day, my old friend Majeed – he’d boarded an illegal vessel, crossed the seas into the Gulf and come back a rich man – asked me whether I’d consider sending her to work as a kitchen help in the big house he had rented. She had to work from 7 a.m. to 6 p.m., and she would be paid thirty rupees a month, he said. In those days, that was a considerable sum of money – you could buy biriyani in a restaurant for three rupees.

My wife was pleased, but I felt a keen sense of embarrassment in sending my daughter to work as a servant in Majeed’s house. But what to do, we had no other option. My daughter lasted only five or six days in her new job. Majeed’s wife was a horrible person, and she beat my girl senseless for accidentally breaking a plate. She came back home with her eyes all puffy and red, and angry welts on her skin from the coconut leaf spine Majeed’s wife had used to beat her. It was not rage that I felt, but a deep sorrow and fear. What kind of fate was this! I couldn’t sleep that night.

To be honest, finding a job wouldn’t have been difficult if I could have made myself leave the house and venture into town. I could have asked in the couple of general stores nearby, or gone back to rolling beedis. But the problem was mustering up the courage. I tried my hardest to be brave, but I was overcome with thoughts of danger, that some people were plotting to kill me.

Half a mile to the east of my house was a small market. The beedi company where I used to work was in this market. Sometimes, I’d walk up there and sit for a bit in the chai shop run by an old acquaintance of mine named Poocha Kunjambu. Kunjambu was a good sort, always gave me a glass of tea and a piece of puttu. One day, as I sat in the chai shop, I noticed people, in ones and twos, going up to the room above the shop across the road. There used to be a homoeopathic clinic up there, but the doctor who ran it had moved his practice to Thalassery. Someone seemed to have started a new enterprise there. I asked Kunjambu about it.

‘A swami has rented the room,’ he said. ‘They say he has some special divine powers. He even identified the culprit in a theft case which had no witnesses.’

‘Nonsense!’ said a man having his tea. ‘These are con artists making up stuff to take people’s money!’

Kunjambu disagreed. The swami did not demand any fees, he said, and anyone wanting to pay for his services could do so of their own volition by leaving whatever amount they wanted in a plate set aside for the purpose. Evidence that he had no financial interest, he argued.

For the next two days, I sat in Kunjambu’s shop and watched people going up to consult the swami. Many of them came into the shop for a glass of tea after their meeting with him, and they had wondrous stories to tell. Most of them were Hindus – there were only a handful of Muslims among them. On the fourth day, I put a one-rupee note in my pocket and climbed the steps to the room above the shop.

The swami was a short man, with a shaven head and a forehead smeared with ash. He was sitting with his legs folded on a red cloth spread on the floor, dressed only in a cotton towel around his waist. Another man, dressed in a shirt and a mundu, stood next to him holding a slate and a piece of chalk.

The swami looked carefully at me. I took the one-rupee note out of my p

ocket and placed it in the plate in front of him. He raised his right hand and began gesturing with his fingers. The man in attendance watched his fingers and began writing on the slate. When the swami lowered his hand, the man held the slate up to me.

‘You must find a job immediately,’ I read on the slate. ‘Begin changing the current dismal situation of your life. The future is bright. You will travel across seven rivers to a new land, and become a man of significance.’

4.

As I came down the stairs after my meeting with the swami, I was in a different world. What was this new land across seven rivers? Where might that be, and how could I get there? And how would I become a man of significance when I got there? Nothing was clear, but I felt a sense of hope, of elation. I crossed the road and looked back at the room above the shop. The stairs glittered as though they were made of gold.

‘You must find a job immediately. Begin changing the current dismal situation…’ The swami’s words echoed inside me, and as I stood there thinking about it, Jadayan Vaidyar came along. People have long forgotten his real name, and all of us called him Jadayan because of his matted hair. As a child, I was often sick with asthma, and Umma always said it was Jadayan Vaidyar’s medicine that cured me. It was he who treated Umma towards the end of her life.

Jadayan Vaidyar had a large body and dreadlocked beard and hair. He was not in the habit of wearing upper garments. In his saffron mundu that came to his knees, sandals made out of pieces of old tyre, and a small cloth bag of medicine bottles, Jadayan Vaidyar cut a striking figure. He looked exactly as I remembered him from my childhood – the only change was that his hair and beard were now grey. He had never married. His only family was a sister who was also unmarried, and there was some distasteful talk about their relationship, although no one said anything to his face. There was barely anyone in our village who had not experienced his benefaction.

‘What news, Amu?’ Jadayan Vaidyar stopped in front of me. ‘Are you not working now?’

I said no, and he said he had a job for me.

The shop below the swami’s room was vacant. Jadayan Vaidyar had rented it and was going to open a vaidyasala, and he was offering me the job of dispensing medicines to his patients. I told him I knew nothing at all about medicines, but he didn’t find that to be a problem. ‘I’ll prepare all the medicines at home, put them in bottles and jars, and label them appropriately,’ he said. ‘All you have to do is look at my prescriptions and give the patients the medicines I have prescribed.’

And so I became the medicine dispenser in Jadayan Vaidyar’s vaidyasala. Twenty-five rupees monthly salary, and two rupees per day for expenses. Six months I worked there. Then one day, as I went to open the shop, I saw a bunch of people in front of Poocha Kunjambu’s chai shop, forcing him to shut it. I stood aside, not wanting to get involved.

‘They got to Kunjiraman in Neerveli,’ I heard someone say. ‘He was among those who stood guard over the Meruvambayi mosque, protecting it. That’s what they’re pissed off about.’

‘They jumped on him calling him Muslims’ spawn,’ another man said. ‘He died on the way to Koothuparamba Hospital.’

Fear engulfed me. It was around 10 a.m. Jadayan Vaidyar spent the morning making house calls and only came to the shop around eleven. I did not wait for him and went straight back home. My wife asked what happened, but I didn’t tell her anything, just that I wasn’t opening the vaidyasala that day.

The certainty that I too would be killed one of these days took hold of me, and I was paralysed with fear. I lost the courage to get out of the house, let alone go to the market to open the medical shop. A couple of days later, Vaidyar sent someone to find out what was going on, and the next day he came to check on me himself. I told him I’d taken a job in a hotel in Thalassery and that I couldn’t work for him any more. My wife and my sister couldn’t understand what had happened to me, and I didn’t tell them anything.

I didn’t step out of my house for the next two weeks. Except for frequent glasses of black tea, I hardly drank or ate anything. Sleep was elusive, and the restless nights left me dejected and lethargic during the days. Finally, one night, I left home quietly and walked to the maqbara – the place where I’d witnessed several wondrous things. It was pitch dark, around two in the morning. I lit the candle I had brought with me and sat down. A gentle, cool breeze blew, and my eyes closed as tiredness overcame me. Suddenly, in the dim light of the candle, I saw a shape – a thin, elongated shape like that of a serpent. It came towards me, but surprisingly, I felt absolutely no fear. After a while, I felt that the shape had a human form. Not a clothed form, but almost like a shadow of a human being. It came close to me and bid me salaam.

‘Wa ‘alaykum as-salam,’ I returned the greeting.

‘Is your life good?’ asked the shape.

‘Alhamdulillah,’ I replied. Praise be to God.

The shape began to speak. What it told me was information about some medicines. Of those, three were ones I was already familiar with, and four were medicines that I’d never heard of before.

The three medicines I knew of were antidotes for poisons – for spider’s poison, snake venom, and for kaivisham, the poison secretly fed to a person as part of witchcraft. The other four were remedies for sicknesses like leprosy. You must always find a way to help the poor souls with no means when they come to you, the shape advised me. It then told me where to find the healing herbs and other ingredients to make these medicines.

As I walked back home from the mosque yard that night, someone whispered the name of the land across the seven rivers in my ear. It was Theeyoor – this land. And that’s how I came here. In those early days, my friend Beeran helped me. And it turned out that it was Beeran’s nephew who became my first patient. The young man was suffering the effects of kaivisham given to him by a Thiyya woman. I treated him successfully, and brought him out of its effects. Since then, I’ve cured leprosy, madness, many kinds of spirit possession … There have been a few problems that have eluded me – mostly those caused by a curse or brought about by trickery…

At this point in his narrative, Amu Jinn straightened his back and sat up, his face suffused with the light of accomplishment. When he spoke again, his voice seemed to echo.

‘I’ve endured a lot,’ he said. ‘When I see others who are struggling, I remember my own struggles.’

A couple of times, as he was narrating his story, a thin, tired-looking woman who might have been his wife had come to the door and peeped inside. Each time, I expected her to say something but she did not.

By the time Amu Jinn came to the end of his story, Ravi arrived. He beckoned me outside, and asked, ‘How did it go? Did you get what you wanted?’

‘Oh yes, quite a bit,’ I replied. ‘I didn’t ask him anything. Just let him talk freely.’

‘Well, you should give him something. He doesn’t have any personal income these days.’

‘What would you suggest?’

‘Ten or twenty rupees should do it,’ Ravi said. ‘It will be of use to him.’

In the end, I gave Amu Jinn fifty rupees. Darkness was beginning to settle when I finally packed up my tape recorder and said my goodbyes.

‘I’d like to meet this man Beeran,’ I told Ravi as we left.

‘Which Beeran?’ Ravi asked.

‘He’s a shopkeeper, that’s all I know. An acquaintance of Amu Jinn.’

‘Ah yes,’ Ravi said. ‘I know him. Lives near the beach. Not that we’re friends or anything. Why do you want to see him?’

‘It turns out that he had a part to play in Amu Jinn’s arrival in Theeyoor. I feel I need to speak with him, too, to get a fuller picture of Jinn’s life.’

‘Well, in that case we can go right now,’ Ravi said. ‘He doesn’t have his shop any more. He’s now a teacher, a gurikkal.’

‘Of what?’

‘Muslim folk arts – Kolkkali, men’s Oppana, Mappilapaattu … And he’s doing really well, now that interest in folklore and

folk traditions are having a renaissance. There’s an organization near the beach named Ambiya Muslim Music Group. Beeranikka usually hangs out in their office.’

We walked to Theeyoorangadi, which was about a kilometre away from Amu Jinn’s house. From there, we took an autorickshaw to the beach – a further two kilometres away – and got out outside Valiya Palli, the big mosque. The place looked much more affluent than the market area. The main street was not as crowded as the market street, but it had all the signs of wealth – modern, high-end shops on both sides, a pleasant fragrance in the air, the sound of stereo music, rosy-skinned people dressed in shiny clothes…

‘This place is nicknamed Bombay. Guess we should say Mumbai now,’ Ravi said, laughing. ‘Everything you see is the result of Gulf money. People from around here must have been the first from Kerala to have gone to Gulf countries to make a living. Even those who sneaked in on illegal boats are millionaires now.’

But we didn’t have to go far for the atmosphere to change. Leaving the main street, we stepped into the sand, into a narrow lane. Here were traditional houses with shell-shaped roof tiles, low-slung, palm-leaf thatched huts, small shops … It seemed as though, in just a few steps, we had stepped back in time.

Ravi and I had fallen silent somewhere along the way. The roar of the waves, the brisk sea breeze and the lowering darkness formed a shroud of inchoate sadness that settled over me. It was a feeling I was familiar with – every time I was in surroundings like this, I found myself suffocating under a cloud of indescribable sorrow and anxiety, each passing moment painful to endure as I would be steeped in a sense of loneliness and insecurity.

Presently, Ravi and I came up to a narrow road between a couple of ice factories and a few fish-processing sheds. Ravi pointed to a general store with a small group of people in front of it. Above it was a board with the words ‘Ambiya Muslim Music Group’ written on it. ‘There,’ he said, ‘that’s where you’ll find Beeranikka.’

Theeyoor Chronicles

Theeyoor Chronicles